In the early morning darkness, as the before-bed bourbon transitions from sedative to stimulant and my heart loses its sense of rhythm, I open the cabinet above the stove, bypass the childproof lock on the ibuprofen bottle, and hear the soft, sucking sound of your bare soles on the tile. The pills fall from my hand as you approach. Barbed-wire tattoos cuff your wrists, but otherwise you seem younger, no more than a girl and thin as a pin oak. Only when you’re close enough to touch do I notice the stone lodged in your left ear, the awkward angle at which you hold your head.

For a moment, you speak unintelligibly, addressing the knife drawer. Then you reach into your mouth and remove from your tongue a large, yellow leaf, which you hold out to me like currency, your penny-colored eyes locked on mine.

Got anything to drink? You say.

As I pull a bottle from the freezer, I ask: Who killed you?

You tell me: Don’t be silly.

You tell me: I’m not dead.

*

One humid summer evening, Uncle Jimmy balanced a condensation-coated Corona on your belly. It’s a vacation, he said. You were thirteen, good at reading, math, and swimming; you were not good at fun. You took a sickening sip, set the beer aside, and did not pick up another for seven months, and then only to wash away the ash-flecked taste of your first kiss.

Later that year your father asked you to sit beside him in his leased 1965 Mustang, which he’d outfitted with an oversized amp and a Pioneer sound-deck. You listened to The Who, The Stones. Eventually he put on Hendrix and told you to go inside, to shower and call your mother. Then he called you beautiful and told you to close the door.

*

You were the best diver on your high school squad. Belief is the hard part, you told me later. Keep your chin tucked, trust the water.

One bleary-eyed Sunday morning, you heard a battered woman describe her taste for living water, the way the divine had called her name. Then, without warning, He called yours. The pastor emphasized the personal responsibility that accompanies salvation. What God wants, he said, is for you to understand what you’ve done, and to understand that He can fix it. What had you done? Abused the Lord’s name, secretly secured a prescription for birth control pills, engaged in deeply unsatisfying pre-marital sex, hated your dead father and living mother and the town in which you were raised, stayed drunk Saturday nights and hungover Sunday mornings, equated transcendence with the knifing sensation that accompanied a flawless dive.

His flag lapel pin cut into the bridge of your nose as you cried into his shirt.

*

During your freshman year at college, a heavyset teacher in Coke-bottle glasses outlined a philosophical and biographical explanation of Ernest Hemingway’s suicide: genetics, electroshock therapy, Stoicism. You aced the exam but presently fell for an answer-copying classmate, a towheaded boy who’d suffered a baseball injury as a child that left him, he assured you, sterile as a surgeon’s scalpel.

You were nineteen when your son emerged vernix-coated and screaming.

Your son had a rare eye condition called retinoblastoma. Your mother taught him to pray.

*

We met at the probation office. In the courthouse parking lot, I slid my hand under the hem of your sun dress.

You said: We can’t have sex unless we marry—I can’t drink—I have a problem—I have to be a good mother to my child.

I said: Yes, we can. I said: No, you don’t.

We were twenty-five then.

You claimed you’d been a wild drunk. The girl who had to be drugged and smothered before she fell asleep. The girl no one left alone with a boyfriend or a liquor stash. You spoke in the third person, describing a character decidedly not you, a character I didn’t buy, whom I believed you’d stitched together from television and tabloids, other people’s stories.

I said: What if I wear a condom?

You said: I just can’t.

But a DWI following a stop for a burnt-out blinker could’ve happened to anyone: You’d never had a real problem. You’d never lifted your shirttail to reveal a barbed wire wound sustained mid-blackout when, according to reliable sources, you’d tried to jump a fence with a gin bottle in your fist, howling out a George Strait song as you bled in a patch of buttercups and cacti. You’d never tossed candy-fat Christmas stockings into the fireplace and pinned your father against the fridge and threatened to crack his skull with your grandmother’s snow globe while it tinkled the tune to God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen.

You’d never been me.

*

Nine months sober, at a New Year’s Eve party, you asked me for a drink—just one, to prove something to yourself.

On a bunk beside a kitchen sink in my cousin’s old RV, I came quickly, sweating booze. You mopped between your legs with a hot pad you found in a drawer. You pulled down your sparkly dress. You went back outside, opened the trunk of my car, grabbed the whiskey, and killed a quarter of the bottle with one long pull.

I didn’t know you could dance until that night.

I didn’t know that two weeks earlier, you’d emptied your savings account on an experimental procedure which might restore your son’s sight. Didn’t know the operation had failed, that your son had taken to wearing a patch, and that on Christmas day, before supper, he’d refused to participate in blessing the turkey and gravy and hot-buttered rolls, refused even to say amen.

And I didn’t know that, while my cousin and I snorted Adderall in the bathroom, you climbed onto the railing of the back deck, balanced as though standing on a diving board.

I know now.

I know this:

You kept your chin tucked. You thought, perhaps, of your father, your child. His father. Your pastor. You thought of me and Ernest Hemingway. Seneca, maybe.

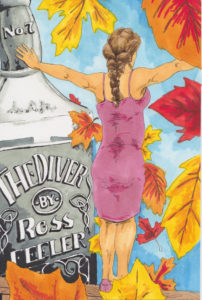

At the last possible instant—I know without having seen—you pulled back your arms.

Then I hope you quit thinking and found something in which you could believe.

Your body, your talent. The knifing sensation. The perfect dive.

*

You say: Don’t be silly.

You tell me: I’m not dead.

You ask me for a drink.

I dab the sweat beneath my eyes.

For a moment, I alternate my gaze between the bourbon and the kitchen sink.

You hand me a softball-sized globe full of autumn leaves instead of snowflakes and as I turn it upside, you pour each of us a drink, three fingers on ice to help wash down the pills. Leaves float into the sky, gathering in the top of the bowl, swimming in water.

Now let’s flip it, you say.

We can’t, I say. I have to get some sleep.

You tell me: Yes, we can.

You tell me: No, you don’t.

Ross Feeler’s writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, The Potomac Review, Hypertext, New South, The Common, and others. His novel-in-progress won the 2019 Marianne Russo Award from the Key West Literary Seminar. He reads slush and writes the occasional blog post for The Masters Review.