Cora J. Duffy

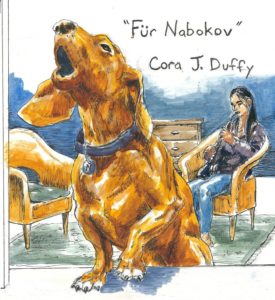

When cuddles; idle threats to muzzle; all-natural ingredient, calming effect milk bones; the ThunderShirt with money-back guarantee; that corrective sandpaper sound the Dog Whisperer makes; NO; and the cold shoulder failed, Nabokov took up classical music. As a result, he no longer screams through Texas thunderstorms. He chills with Brahms, Shostakovich, and Yo-Yo Ma. Considering my dog’s namesake, one would think Nabokov—ten years, dappled, short-haired, male, neutered—to be a wordsmith in many languages in addition to his native tongue. That was, after all, my intention, thinking “Nabokov” would somehow channel writerly genius to me vis-à-vis my dachshund. But instead, though no less brilliant, my Nabokov’s expertise lies, not in words, in music. Concertos, sonatas, and chamber quintets, his wheelhouse. This discovery being the happy by-product of finding, finally, a way to weather the Lone Star State’s storms.

North Texas endures fifty thunderstorms a year, a fact Nabokov did not consider when I was popped the question: will I make my Dallasite boyfriend my husband, pack up the doghouse, and transplant our shared existence, Writer-Wienerdog, from home to here? Nabokov was in love, so in making his decision he did not chew over such factors as tornado season when twisters show off, somersaulting semi-trucks overhead like a trampoline flings upward double-jointed acrobats. Nor that cold fronts collide here with pent-up Gulf Coast humidity, frequenting late afternoon and overnight rains. Thunderquakes jar the bed as you grapple sleep. Lightning cracks open the sky at blinding rates up to eighteen flashes per square mile. It was all to be expected. But my dog grew up in sunny Southern California; Nabokov has no tolerance for any of this.

Yet, Nabokov moved to Texas. I married. And since, from the apartment where Nabokov and I now live and work and have very little social interaction aside from with one other, we listen to classical music. Classical is a veritable wonder tonic for humans—it lowers blood pressure, masks the perception of pain, facilitates language and memory recovery, improves mood. I am unsure if it kicks homesickness, but classical focuses concentration and reduces stress. It was my learning all this that made me think to play classical for Nabokov during storms in the first place. Nabokov has seen two hundred plus days of Texas gray skies since our move. Subsequently, as it is the only effective remedy I’ve found for easing his anxiety, he has spent fifteen hundred plus hours immersed in classical music.

Before classical, thunder dropped the downbeat, 1, and Nabokov kept time, 2-3-4, in perfect metronomical barks. Now, classical turned all the way up provides the soundtrack, the score hanging jewels on the tempest outside. Classical hits Nabokov like a tranquilizer dart. He basks in it, meditates on it, and zones out the storm. (Ironic, as Nabokov, the great talent, the two-legged one, respected but did not enjoy classical music. “When I attend a concert—which happens about once in five years,” Vladimir Nabokov said to Playboy in 1964, “I endeavor gamely to follow the sequence and relationship of sounds but cannot keep it up for more than a few minutes. Visual impressions, reflections of hands in lacquered wood, a diligent bald spot over a fiddle, take over, and soon I am bored beyond measure by the motions of the musicians.” And in his autobiography, Speak, Memory, again: “Music, I regret to say, affects me merely as an arbitrary succession of more or less irritating sounds. Under certain emotional circumstances I can stand the spasm of a rich violin, but the concert piano and all wind instruments bore me in small doses and flay me in larger ones.” I suppose Nabokov, the two-legged one, hadn’t the patience for classical music. Or an exigency. He said he hadn’t the ear. Another irony in light of the pop, the chord progressions of his prose:

How he wrote of “heat lightning taking pictures of a distant line of trees in the night” and how “rain, which had been a mass of violently descending water wherein the trees writhed and rolled, was reduced all at once to oblique lines of silent gold breaking into short and long dashes against a background of subsiding vegetable agitation”!)

Fifteen hundred plus hours my dog has listened to, focused on, classical music while here in North Texas. A concept researched by Dr. K. Anders Ericsson, and popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in his book Outliers: The Story of Success, rules that if you practice any one thing for ten thousand hours, you master it. “Maestro” is what you call a master of music. (“Vladimir Nabokov,” a master of words.) Ten thousand hours at the generally accepted ratio of seven canine to one human equals one thousand four hundred twenty-eight-and-a-half hours when calculated in dog years. This sum is bested by my Nabokov’s fifteen hundred plus.

Maestro Nabokov commences his music studies from his crate, burrowed in fleece blankets so thoroughly washed their fluff has worn to an even pill. He likens his den to a mommy’s tummy, and therein his experience of classical music is that of a baby in utero being played Amadeus through carefully situated prenatal headphones. Nabokov’s music plays from a portable radio with speakers on all sides and extended battery life. He dials in to local broadcast station Classical 101.1-WRR, and piccolos and violins outsing the trill of gale-force winds. Thunder rolls are swallowed up into the potbelly of the tuba. Schumann, Symphony No. 1 in B-Flat Major ‘ Mozart, Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor ‘ Mendelssohn, Fantasie in F-Sharp Minor, Opus 28 ‘ Chopin, Three Nocturnes, Opus 15 until the storm system is pushed northeasterly by a squall line of masterworks ‘

Nabokov is not the only dog to find sunshine in classical music. In a 2012 veterinary science study, one hundred dogs, including thirty-four dachshunds, trembled en masse to Judas Priest, but when Air on a G String crooned for their kennel, Dr. Lori R. Kogan found her test subjects tucked chins to paws and listened in quiet satisfaction. And Peps. Peps the cavalier King Charles spaniel would sit on a stool next to Wagner’s piano and wag his tail to melodies of his liking and moan to those needing work.

My dog has this musical acumen. He likes harps, though not harpsichords. He loves legato. He does not like pieces played by the organ. He finds organ music grating—indistinguishable from a fire truck horn. Symbols too he could do without. 1812 turns up his nose; he expressly opines it “overrated.” And then there is—splendiferous!—the first movement of Moonlight Sonata. It transports him: “It’s just me with Squeaky Duck set afloat on a sea of peanut butter.” If given the chance, Nabokov would choose the Romantic over any other era. “The Romantics painted dreamscapes,” he broods, while I, Writer to his Wienerdog, compose sentences at my desk. “They wrote from the gut.”

Nabokov knows far more about classical music than I do. They say you get out of it what you put into it, and he simply has put in more time. Only about seven hundred and fifty human hours have my efforts racked up in piano—two years, once-a-week, I stretched hands, large for an elementary-aged girl, across the whites of the church upright, because we had no family piano on which to practice scales at home—and clarinet—two equally lackluster years in middle school—combined. Not to mention, my stints in both instruments were uninspired, so arguably my piano and clarinet practice hours shouldn’t count towards mastery at all. (Uninspired, by that I mean, when compared to my obsession, age eleven to thirteen-ish, with the cor anglais, the instrument that shares my name but is more commonly called the English horn. The English horn is not, mind you, the more popular French horn, that back row, brass instrument shaped like an at-sign symbol. It was always the blessed French horn of which people thought young Cora spoke. But no, I ached to play the English horn, the alto oboe, a double-reeded woodwind, unbeknownst to me, not regularly included in music arrangements.

I sketched its gangly, bulb-ended silhouette on every notepad and Post-It within reach. I drew its sloped neck, its slender shaft, its cormous base like a lovesick teen scrawls her Christian name smashed against the surname of her first beau. My sketch of the English horn looked like an erect penis. I was innocent to this at the time—forever a late bloomer. So, shamelessly I littered English horns around our house as deliberate little hints of my desperation to blow one.

My parents did not buy me an English horn.

Unlike Nabokov, I didn’t grow up in Southern California. I grew up in rural Kentucky where, aside from our town’s few public school music teachers and my former pianomarm, I was likely the only soul in the county who knew the English horn existed. Or, at least, this was the truth adolescent Me liked to believe. Force-fit, as I saw it, into a cultural abscess of a hometown, I needed the English horn. I sought to sound an alarm, an open, elegant, melancholy howl, so the beautiful outside could find and rescue me. But for no reason I could ascertain, my parents stood staunchly against buying musical instruments.

I did farm chores and hoarded my lunch money to save up to buy my E. horn myself. But there was room for only one double-reeded woodwind in the middle school concert band. And a second year got upgraded to oboe from flute. This bitch had flatter teeth than me. Do flat teeth outweigh passion when it comes to double-reeded instruments?

Destiny had kicked me in the buckteeth. The best I could do, and had to do to save face in the wake of my Post-It campaign, was buy a secondhand clarinet with my hard-earned cash, unemphatically learn its fingerings, and convince myself it was a steppingstone to the English horn—I have yet to get.

Nabokov, my phallus of a dog, asserts, “It is never too late to pick up music.” Indeed, his studies of classical did not begin until long past his puppyhood. After I ran off from Kentucky, set up with him in California, committed to writing, only to drag us half the distance back from where I started, here to Texas, it was after that when Nabokov, out of necessity, got into music. As of late, I have searched “cor anglais” on eBay and wondered in what posture Nabokov would sit during my lessons.)

Nabokov is an auditory learner. He attributes his education of music history and theory fundamentals to a nationally syndicated radio show called Exploring Music with Bill McGlaughlin. Nabokov listens to Mr. McGlaughlin’s carefully curated songs and commentary whenever it rains around suppertime. Mr. McGlaughlin’s voice, mezzo-piano but with a lift of enthusiasm easily mistaken for mischief, is exactly how I imagine Nabokov’s voice would be if he were to speak and not be a dog.

Nabokov sometimes howls in his sleep—not bombastic, bottom-heavy, whole note howls, just half note howls. This too has been since we moved to Texas. Howls are said to be expressions of canine loneliness. Could it be my Nabokov cries out in his dreams in an attempt to assemble a pack, in need of another friend? No, when Maestro Nabokov howls in his sleep, it is because he dreams he is prompting the orchestra to tune. (Only to drag us half the distance back from where I started, by that I mean, sometimes I exaggerate, even misconstrue things, when living in isolation.

I also turn to music. For example, in high school after I gracefully retired from clarinet and ostracized myself from concert band, I clung to a new love affair, a sort of music orgy compulsory to girls my age but of a generation before mine: John, Paul, George, Ringo. I discovered the album sleeve of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and the English horn in the grasp of bristle-lipped Paul. This English horn was to me a sign from the music gods: “Give the lads a listen.” Cloistered up in my room after school; after driving the tractor for my dad on Saturdays; after church; after I had begun to count down until the morning I could leave my small town and seek out highbrow people, places, and things; I danced my way through The Beatles catalog. My bedroom door and eyes closed, I mouthed every melody, and, so free, I danced.)

When Nabokov is not studying music, on dry days, during hops-smelling North Texas noontimes, or amid one of those magnificent fuchsia sunsets that reels across the sky as if the sky is a drive-in movie screen and the movie the most compelling you’ve ever, ever ‘ he frames himself with windows. He sits on the windowsill and looks out. I am not sure what he looks or listens for—bull toad symphonies? the inevitable next storm front? ghosts of cowboys calloohing campfire songs? lepidoptera? But I do it too. In fact, if I have spent ten thousand hours practicing any one thing, I’d wager it is looking out windows. The boyfriend before my Dallasite boyfriend that is now my husband diagnosed my looking out windows as greener pastures syndrome. Maybe. Or, outside the window is where ideas live. I like to think inside the window to be the workshop, solitudinous, be it not for the artist’s lapdog or studio cat. Cats, how they must hate music, those eaters of songbirds and lifters of tonedeaf mews…

When in our Texas isolation I read Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear and she explained that “the Greeks and the Romans both believed in the idea of an external daemon of creativity—a sort of house elf, if you will, who lived within the walls of your home and who sometimes aided you in your labors,” I smiled at the thought of Maestro Nabokov decoding key signatures at my feet while I once again wrestle a semi-colon. Because, since Nabokov and I moved to Texas, we have spent more time together than ever before; we do our work. “The Romans had a specific term for that helpful house elf,” Gilbert said. “They called it your genius—your guardian deity, the conduit of your inspiration.” This was funny to me, like when years after picking my dachshund’s name, I learned Vladimir Nabokov himself had had dachshunds.

There is an enduring pattern of artists working alongside their pets. Lump was to Picasso what Sackcloth and Ashes were to Mark Twain. Twain even described in his autobiography his little helper kittens as “such intelligent cats.” And Peps. He was Wagner’s genius. Peps—void of the cunning of people, trustworthy, sensitive, erudite, a devotee—above all else, Peps gifted companionship to Wagner whose workaday, like mine, otherwise unrolled in solitude. That’s my point. For all one knows, this construct, Artist-Genius, Maker-Mutt, Writer-Wienerdog, exists to ensure art is not made in a vacuum, not made in a vacuum after you move away from your home and humans. It is a relationship of codependency. The Peps motivate and in exchange the Wagners try to deliver music worth critiquing, lavishable music when deemed by the Peps as “good.”

It is windy outside now. Nabokov is pacing from his crate to the window of the back patio door. I queue up “Cool Down Classical,” a playlist on Amazon Prime. With the volume pumped: Rachmaninoff, Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Minor, Opus 40: Movement II, Largo. Nabokov keels over onto his pillow by the door and curls himself into a sausage ring. This is how he gives the piece of music, its ability to mute the storm abrew outside, and the interplay between nature and song, his equivalent to the standing ovation. He smacks his mouth in triplet and submits to hypnagogic eyes. Have I mentioned Nabokov also learns through osmosis?

I have seen MRI images of the brain’s activity when a person listens to music. These images look like Doppler radar. The MRI assigns different colors to various levels of stimulation and the brain map lights up—a tornadic supercell of music moves in. When Nabokov listens to classical music, like he does right now, I imagine the colors and animation of his brain map. I’d say his is a full coverage of colors, a blossoming accelerando with multiple hook vortices and bow echoes.

When Nabokov and I listen to music together, I like to think our brains light up synchronously. At this very moment, we might make the same colors. Some poet said, “Classical music is orchestrated emotion, song unadulterated by logic.” Nabokov and I might purely feel the same thing?

Emory University researcher Dr. Gregory Berns performs pet-friendly MRIs on dogs. Though he has not, to my knowledge, tested dogs under the influence of classical, his research has revealed that the active area of the brain associated with emotional response in dogs and in humans is the same. I switch to a playlist designed to boost our brainpower.

Outside, a young mesquite tree arcs sideways under the wind. I tell Nabokov, “You are living in exile from your homeland just like your namesake did.”

(I grew up in rural Kentucky, by that I mean, I’m proud to have been raised in Kentucky. This realization I came to after moving away. My discontent there had nothing to do with Bluegrass culture, for it does not lack art or richness, but with how culture at large promises something unexplored, and how we can’t say for sure, but it is possible, that that alone makes it more attractive or better, or perhaps, my discontent was something else entirely, some issue, a high-lonesome sound inside myself I still have not figured out. Also, when Nabokov and I left California, we knew we’d spend lots of time off on our own.

The madness that is creative lightning requires time and a secluded place in which to wait for it to ground. When asked by the London Sunday Times in 1969, “Do you feel isolated as a writer?” Vladimir Nabokov answered, “Isolation means liberty and discovery.”)

I am holding my dog in my arms now and we are watching the storm compound. From the window of the back patio door we look out, listening to Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony. Nabokov puts his sweet paw on the window’s latticework. We press our noses to the glass. The rain-hammered surface of the pond outside vibrates with the stretched skins of the timpani drums. Trumpets pulse the yellow enliven of the sky. Nabokov and I, standing here, are Dorothy and Toto, two more in the timeless lineage of farm girl, her dog, and a storm. The English horn solo starts. We look out on a fanciful other place—splendiferous!—the music crescendos and together we anticipate the cloudburst.

Cora J. Duffy writes screenplays, poetry and experimental nonfiction. She holds degrees from Chapman University and the UCR-Palm Desert low residency MFA in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts. Formerly she has worked in post-production at Sony Pictures and as the Associate Poetry Editor for The Coachella Review. Guidebook Out (of the Ordinary) is her travel writing and film review project on Tumblr.