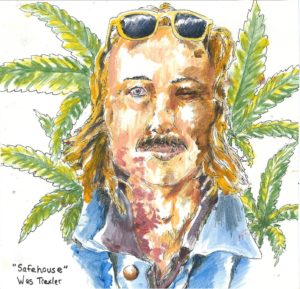

Wes Trexler

When Goody comes over we head straight for the basement, sunglasses perched on our domes like cheap plastic tiaras. At the bottom of the stairwell I open the door and a spectrum of blue-yellow light leaks out with solar intensity. We drop our shades and go in squinting, until our eyes adjust to the Mylar spectacle of lamps and plants and felonious biology multiplied by reflective walls.

“Look,” I say, “This one had a grey spot of mold on the cola yesterday.”

“Botrytis,” says Goody.

“Right. So, I lopped the top off, took it upstairs. Today, it’s all over the place.”

“Fast.”

“And it’s been sixty-one days, so, ain’t much to gain by lettin’em go any longer.”

Down here in my basement I can feel the juice, the ballast hum buzzing my eardrums. There’s a harmonic vibration with all the equipment oscillating at some-dozen hertz, and it adds to the physical buzz of illegality and risk. As Goody and I stand, taking one final look at this crop, I feel like I always do. Like we’re on the verge of something inevitable, about to slip into an absurdist vérité way beyond our control.

We go to work, dragging them into a side room one at a time through a doorway covered by two sheets of black plastic. When we get about twenty plants pulled aside, drooping awkwardly in their five-gallon grow bags, sagging with top-heavy buds, I perform the final ritual. I pull one up, then blast the root ball with hot, hot tap water, holding them horizontal so the steam won’t rise on the buds. Grower’s mythology. My dad told me the heat shocks the plant, forces all the juice from the stems into the buds, makes more crystals when they cure. Who knows, but we do it out of tradition, plus, keeps dirt off the product. Tedious work for two hundred little ladies, but, after nurturing them from clones to veg-phase, then budding them out for two months, the extra few minutes of attention is worth it. Sort of meditative too, baptizing each one, their last sip of pure water before they hang to dry.

I hand them over to Goody one at a time, he holds them up, turns them over, studies them, always looking for lessons, hints, inspirations that may help improve the next cycle. When he’s satisfied he cuts the gnarled hemp stump with nippers, chops the main branches from the trunk, then drops them, leaf and all, onto a rubberized Mylar tarp.

By the time we’re done harvesting, the pile is knee-high. Stray branches spill onto the concrete floor. Seeing it amassed like this makes me delirious, makes me glad Gina’s not here to see it.

We both giggle a raunchy little laugh at the sight. For me, at least, it’s a cover for this weary dread I’m consumed with. A horrible joy—relief compounded by justified anxiety. The plants have made it past mite and mold hazards, but now is the worst part, the curing, two weeks at least, reeking worse each day until you almost want the cops to come and end the uncertainty. This is the time, between timber and twenty-sack, that hurts. If anyone’s been on the scope, waiting to gank me, or home invade me, now’s the time they’d do it. For the next fourteen days I’ll be physically incapable of thinking about anything other than the rows and rows of buds-on-a-stick that will fill my office, and half my bedroom, once we’ve trimmed them down and hung them on floss runners.

Goody and I grab the corners of the tarp and try pulling the pile into a bundle, but the grommet ends don’t quite meet.

“Fuckin A,” says Goody.

“Heavier than it looks,” I say.

We struggle for a minute to get it into shape, then hoist it to waist level and make for the stairwell. Goody goes up backwards, dragging the load up the stairs; I lift and push it forward, but, halfway to the top, the bundle gets wedged between the handrails.

“Try pullin back down,” he says.

I tug hard, but it’s jammed. The raunchy laugh leaks out again.

“Nice problem to have,” he says.

Before we can form a plan there’s a knock at my front door. We freeze. A distinct, familiar horror runs through me. I put my finger to my lips and listen. There’s another knock, but it’s friendly, not the arrogant, fascist thump of a Brown Bear. I mouth the words Go see who it is to Goody. As he goes through the kitchen I hear the phone ring, and I know it has to be Bobby Salsa, standing on the porch, cell-phone in hand.

I hear Goody open the door right above my head, then the confused voice of Salsa greeting him, asking for me. I can’t get past the bundle, don’t want to squeeze our primo fluff trying to climb over, so I go back down and out the basement door, come up behind Salsa and push him through the doorway.

“Jeez Louise, where’d you come from?” asks Salsa.

“Nowhere,” I say. My living room looks dark so I reach for a light, then realize I’m still wearing the shades. There’s Sunshine Mix and vermiculite clinging to the hair on my forearms, a wet, muddy rainbow smearing the front of my T-shirt.

Goody and I are both sweating and flushed from working in the hothouse. A black ring of finger hash lines the web of his thumbs and palms, and there’s a three-inch twig with the tiniest wisp of a pot leaf stuck in his mussed-up red hair.

“What’re you guys doing? Look like you been smoking crank down there,” Salsa says.

“Maybe you been smoking crank,” says Goody. It’s meant as a diversionary barb, but we all sense a tone of subdued aggression in his voice. Even Goody seems thrown for a second.

“Fuck crank,” I say. “Let’s smoke a doober.”

We all throw in for a thing that winds up looking like a midget’s T-ball bat. I toss it to Salsa. Then, when he’s looking for the lighter, I get Goody’s attention, try to make him pull the leaf from his hair. He can’t figure out what I mean, so it just dangles there.

I love Bobby Salsa as much as anyone—a sweet guy, raised by a brood of older sisters, totally self-centered in a distracted, hyperactive kind of way, but harmless. Ever since Gina and I moved out of Staddlerville, into this neighborhood I’ve seen the dude two or three times a day, at least. He’ll call and wake me up early, come over and blast his face off with my Erlenmeyer hookah, he’ll swing by later, show me some blues progressions and we’ll jam out for a while, or I’ll go over to his place and help load his bass rig into the Little Guy, his Mazda hatchback.

That car—little red struggle-buggy with the passenger seat pulled out to make room for his Ampeg—that’s how I found out where Salsa lived. The week Gina and I moved to this neighborhood I kept seeing his car parked across the street from my garage. The bare mount bolts on the floorboard verified his ownership. On the third day I decided to knock on the door; sure enough, there’s Salsa raising his heels, blowing smoke rings out the window. Since then he’s been a presence.

Salsa lives with his fiancé, a hellacious, busty fox. She’s a West Virginia carpenter-farmer’s daughter, and her parents choose to believe she’s a twenty-eight year old virgin. Salsa pretends they haven’t been shacked-up for two years, and they live in fear of a surprise family visit. This girl don’t smoke. Not that she minds drugs, (I’ve seen her dust rails elbow to elbow with a bricklayer and come out hortin like an Orec XL), she just don’t want her house reeking. Salsa’s a self-medicated chronic disaster, so rather than rile her he just darts over for a few hubble-bubbles to the face every four hours or so. This wouldn’t be a problem if it wasn’t for certain other arrangements.

Salsa is a full-time slinger. His woman likes the way he burns paper, but gives him so much grief for how he earns it. So, like any businessman Salsa tries to put the risk in someone else’s hands, namely mine. Since I live so close, and he trusts me, and since I’m so easily bought, it was a natural.

He goes through four or five pounds a week. Whenever he makes a pick-up, or someone drops it off, he shoves it in a black backpack and hikes over to my place. We live in a duplex, so every time Salsa comes over he pretty much has to walk through our neighbor’s backyard. When he does, their caged lapdog mutt yawps and they look out their window to watch him and that backpack come to my door again. When he needs some, he either walks back over, or I bring it to him, and right now there’s a worn path in the muddy snow from my door to his. All in all, I’d say there’s nobody in a two block radius who doesn’t know what the deal is, but I get paid in weed or money or both, and even though it seems like twice as much sketch, and it is, this situation keeps Salsa in business and keeps his girlfriend, or fiancé, appeased.

This is the safehouse system: Most or all of the deals go down in one place, and the goods are stashed in another, supposedly secret, supposedly secure location. It’s intended to minimize risk if the Tecs swoop down pounding, or if a junkie slinks in while you’re gone, but the way Salsa employs it there are almost no advantages that don’t involve his own personal issues with his own personal superego. Salsa thinks our place is a good safehouse because he chooses to believe it. He chooses not to notice that my basement is practically radiant with high-intensity lighting, ignores the fact that every couple of months I run into an endless supply of the dankest personal headies in town. Salsa believes on faith that Goody Abshire and I are not running this grievous grow underneath his safehouse because he has to, because believing keeps him happy.

Truth is, we always grow big in the wintertime. That’s when we can concentrate on the indoor, don’t have to split the focus between inside and out, don’t have to worry yet about propagating the hundreds of clones we’ll need come spring. In the winter we can cram more lights in the basement cause it’s cooler, and the spike in the juice bill looks like winter heating draw. We get it done in the winter, when everything seems chiller, everyone’s battened down and tranquilized by snow, even the cops like to stay as warm as possible, ignore the ice-packed side streets. We keep our strains going, the random hybrids and Marc Emery heritage strains from B.C., keep our mother plants alive through the cold months, bushing them out in a closet on twenty-four hour, so that, come spring, we’ll be able to whack cuttings one-hundred and two-hundred at a time. In the winter it’s all about the basement, where the furnace burns through the day like a CO2 generator, and all the re-wiring is easy to do, straight from the breaker box to the growroom. Now that I’m out of school I can devote myself to the ritual, going down every day with sunglasses on to work the plants, to mix up Earth Juice and water them, to pull off some fan leaves, reposition them, check the gas gauge, look for bugs and mold, to turn the soil a bit with my fingers, to read the high/low thermometer/hygrometer. And this winter, more than ever before, Goody and I have our program down, maxing out the potential with soil, on the verge of going hydro. Which is probably why Gina’s not here to help us do the trim. She’s in Florida, visiting the girls, but I think she just couldn’t stand the winter heat, wanted to let this one simmer off without her. This is the most muta we’ve every taken in one swat. The most plants, the most lights and wattage, the best varieties, all the organic micronutrients, all the tanks and fans, the most potential, the most risk and, Allah willing, the most profit.

So, Salsa and Goody and I smoke the joint, shoot the shit until we’ve got Bowie eyes and cotton chops. I tune the radio to the college station for the reggae show, and a minute later, hearing that fuzzy melodica trill, Salsa remembers why he came over in the first place.

“Yo,” he says. “I need that three-prong adapter back.”

“Oh yeah?” I say.

“I’m trying to record the Yamaha straight onto my hard drive. Have to run a cord in from the kitchen for the pre-amp.”

“I’ll get that to you, it’s still in the basement.”

“I’ll get it,” he says, starts to stand.

“Naw, don’t worry about it now. We just kicked up a bunch of dust down there,” I say.

“It’s flooding again,” says Goody. “You don’t wanna go down there, get your shoes wet.”

“Alright, alright,” says Salsa.

We sit for a long second, a loopy dub track on the radio: Lee Scratch Perry humping an echobox. It doesn’t take long before Salsa can’t stand whatever ambiguous vibe he’s picking up on.

“Well, I gotta get going anyhow,” he says. He gets up, walks to the door, then, with the thing half-open turns and says, “Oh, and Teddy Biggs is coming back tonight, so I might need you to camp out for me.”

“As always,” I say.

Salsa winks, shoots his finger at me. He always does this, waits till he’s practically on the porch to talk business.

He smiles, says, “You characters.” He looks at Goody, says, “When you gonna sit in with Dr. Jah again? That shit was tight last time.”

“It might be a while. Things have been hectic,” says Goody. He makes this lunar shaped gesture at his sternum.

“That’s right,” says Salsa. “When’s she due?”

“Eight weeks,” says Goody.

“All right, Champ. You stay outta trouble, then.”

“Hey,” I say. “Call me later, before you come over.”

“Will do,” says Salsa, then he’s out the door, swings it back hard like a caffeinated school kid. It slams. Goody and I both sigh, then we hear the yap-dog, and shake our heads. I pick the leaf stem out of his hair. There’s so many problems with this scene we can’t even bring ourselves to talk about it.

You never tell anybody about your operation, that’s the rule, and no matter what, it seems like everyone breaks it all the time because people like to break their own rules. Me and Goody are pretty good with it, and it pays to be conscientious, but in the end you have to tell someone because how else are you gonna unload fresh trees by the pound? When the gauge looks like ours, like it just came off the dry line, hairy and spiky with white crystals, like it’s never seen a Ziploc, people know. They know the shit hasn’t been jammed in a backpack, probably hasn’t moved any farther than the length of the basement stairs since it was a two-leaf cutting. People know but you sure don’t tell them. Last harvest I actually sat on a pound Salsa got off Goody. It grew from leaf to tree to skunk right below my living room, then Goody took his half home and bagged it. Like six hours later Salsa totes it back to my house in the back of the Little Guy, gives me a cut to sit on it for the night. He had to know.

Salsa’s gonna know about this one cause I plan on busting most of my split out to him at fourteen hundred a QP. He can dump it quick even at that price.

Bobby Salsa gets away with some outlandish prices. Usually it’s mid-grade beaster pounds he sells to a guy he calls Mullet, an older dude that runs a drywall business. The Mullet pays his cheap labor crew in weed at market rate. Bobby Salsa knows this because he used to scrape mud for the guy. So Salsa jacks the price way up knowing the Mullet will pay. The Mullet’s a wiry, ferret of a biker dude and Salsa’s the only dealer he knows who’s not slinging pressed Mexican, so he pays. He pays too much and lays a choice sack on Salsa, but every time he grumbles.

“Sorta has a smell to it,” he’ll say.

“Smells like weed to me,” says Salsa.

“No, kinda like…hay.”

“Well, take it or leave it there, Skippo.”

Mullet takes it.

Some of it always trickles down to me on the safehouse deal, and it’s worth the sweat just for the pure theatrics. Once Mullet gets a whiff of this stank he won’t have dick to say, no matter how Salsa cuts him.

When Salsa jets we go back to the stairway to retrieve the bundle. I yank a few sheaves of weed from the middle, and the load eases enough that it slides out easy, but in the process I whack myself in the face with the mungy fresh bud branches. Crystal trichomes stick to my eyelashes, and the serrated leaf edges leave irritated hatch-marks on my face.

By the time we drag the bundle into the living room, I’m nearly blind, and my right eye is stuck shut. My hands are resin covered and sticky green now, so I can’t even touch my face. I feel my way to the kitchen to wash my hands, but the dish soap is bout empty, what’s left has been watered down twice. I finally end up using a dirty dishtowel to dab at my eyes.

“You OK, man?” asks Goody.

“Never better.”

We decide to get down to a hasty fan-leaf job and hang the things before Salsa reappears. With two pairs of orange-handled Fiskars we go at the pile, just taking off the big, seven-fingered look-at-me-I’m-a-cannabis-plant leaves. There’s no time right now for the full-on manicure trim, no time to cut back the chaff and shape those donkey-dick buds into pure gold-standard Chronic.

Three hours into it we’ve barely made a dent. The pile is still ridiculous and scary, laugh-inducing in its excess and purity. Both the scissors are too gunked-up to use, resin glands gluing themselves to the blades, black hash building up on the orange plastic, and along the cutting edge. Our hands are cramped and numb from gripping the thumbholes in one and branches in the other. All up and down my arms I’m breaking out in little welts and red spots. I imagine no-see-um Indicas mites hopping off the plants, burying egg sacks under my skin, leaving allergenic feces behind. This always happens to me, but never to Goody, these hives I get when we trim a harvest. I swear it’s something microscopic, but it could be my mind, stress and spleen erupting out of me in long red streaks and puffy dots.

We take a break to scrape the blades and make a ball of scissor hash. I drop it in the Erlenmeyer and blast it to the head with big coughing fit hits. This is the first, precious taste of a harvest the grower can make. If you have any pride in what you do you know it’s a sin to try and quick-dry a fresh harvest, so these sweet little balls of love can really prove what kind of shit you’ve gotten yourself into.

While we’re trying to catch our wind there’s a loud, fast knock at the door. My nuts shrink at the sound.

“Fuckin Salsa,” I say. “Told him to call.”

I go to the peephole and look out, it’s dark and snowing now, so I can barely see who it is. A girl’s voice says, “Hello.”

“Think it’s Vicky,” I say.

Goody makes like he’s gonna clean up, but the entire floor is a reverie of leaflets and stems and every chair has a paper bag full of green on it. The tarp is still a two-man job, so it’s really no use.

Vicky knocks again, louder, faster.

“Just let her in,” he says.

When I open the door Vicky, still on the porch, cries in a loud stutter, “I just about got arrested! Oh my god, I almost went to prison.”

I pull her inside. She’s shaking and crying, hysterical with spirals of fluffed snow hanging in her straight, blonde hair. She sees Goody, seems relieved.

“Oh God. Goody, I coulda gone to prison.” She drops her black backpack by the door and, for the first time, notices this explosion of grow evidence splattered before her on the floor, and everywhere. “Oh, crap!” She starts shaking worse.

“What happened?” I say.

“I just got pulled over. Old lady called the cops on me for road rage. I should be in jail right now!”

“Jesus, shh. Not so loud,” I say.

“Fuck it,” she says, “I shouldn’ta come here. I’ll leave.”

“No, just sit down, it’s cool,” I say, clearing a seat for her, dumping a newspaper full of scraps into a brown paper bag. “When was this?”

“Just now, they followed me off the exit.”

“Followed you?” says Goody. “How far?”

“Just to McDonalds.”

Goody and I glance at each other. That’s close.

Vicky starts yanking things out of her backpack: jackets and books, a clear vinyl cosmetics bag. Underneath is a sealed Ziploc with two pounds of shrooms. She flings that on the floor, keeps digging till she pulls up a pair of socks, mated into a sphere.

“Look,” she says, revealing a little baggie full of pills. “A hundred morphine.”

“Yikes,” I say.

“Road rage?” says Goody.

“This old bitch was going so slow in the pass lane, I had to pull around her. I was so pissed I got in front of her and just coasted for a while. Oh! Can’t believe…”

She’s still shaking, but now, with the morphine in her hand, she’s stopped crying, which is a relief to me.

“You mind?” she asks.

“Have at it,” I say.

Vicky takes one of the pills and folds it in a twenty-dollar bill. She lays it on the coffee table and pounds it with the Bic in her fist. When the pill is cracked, she rubs the lighter back and forth over the bill, crushing the morphine chunks into a snortable powder. She scrapes the beige dust off the bill, then rolls it up. She whonks it all in a single, relieved insufflation off the glass tabletop.

It looks painful, and I know that it is, but the instant flow of relief melts down her body like the snowflakes dripping off her hair.

“You want to buy some?” she asks me. Her head is tilted back and her voice is nasal and lower now.

I’m not into it.

Vicky crushes another pill and offers half to Goody. He pulls it, but has to use both nostrils, takes him a while.

“Deviated septum,” he says.

At first it seems like a slight, that she gives to Goody what she’d only sell to me, but I know there’s history there, they’ve known each other a long time, so I don’t let it rub me.

Vicky’s like us, another Jackson County wild-child, transplanted up to Mon County, lured by the illusory prospect of getting a liberal arts education, and also by the very real year-round, nonstop party scene that’s been thriving here since the ‘60s, with all the incumbent supply streams and income sources. But she’s from Ravenswood, a creepy little town that crawls up along the banks of the Ohio like an untamed multi-flora rosebush. Everyone in the area knows about Ravenswood girls. They are jagged, and fast, and not necessarily rational. Vicky is no exception. She’s manic and depressive, with a wicked persecution complex and a notorious nymphomaniacal streak that’s easy to overlook, most times.

I’m convinced that Vicky herself isn’t fully to blame for her aberrations, since all of Ravenswood, including the groundwater and the town reservoir, and a large section of the river near it, is on the Superfund list of most dangerously toxic sites in the nation. People said for years there was something in the water over there, but I think they meant it figuratively. Turns out, there really is brain lesion-causing dry-cleaning solution all over the place, all over a town so small that it never, in fact, had a dry-cleaner.

While Goody and Vicky sit draining the drips I start another T-ball bat. This time I rub the hash off my fingers, shape it into a tiny wick, cut it to slivers for the joint. While we smoke, I can hear Morphisto warming up their voices, can see the corrosive agitation in Vicky’s eyes become dilute as the junk sinks in. Before too long Vicky is totally unconcerned about her near miss; she’s looking out the window at the snow, coming at a thirty-degree angle now, quickly covering the path to Salsa’s pad.

“This is like that time out at the Casto’s,” says Vicky.

Vicky tells the story, and I’ve heard it before from Goody’s end, but it’s like hearing the minor variations on a folk tradition. It’s the story about the blizzard of ’91, and about the first time they met, at a party at Doctor Casto’s place. It was the first time either of them got drunk, so they took turns hitting bottle-shots of Jack and jumping off the porch railing into a five-foot snow drift by the house.

“Oh my God,” she says. “That was so much fun. We’d yell something like, ‘Death from above!’ or ‘God save the queen!’ and just dive off backwards.”

“I got so sick I missed the first two weeks of school after break,” says Goody.

“It was worth it,” says Vicky.

Goody agrees. His already-pink complexion gets a narcotic flush from the memory.

I can tell Goody’s lost his drive for the trim, so I pick up the clean scissors and hit a lick on the pile. I do a hack job on about ten dense Blueberry plants, hang them on the floss in my office. Walking back I see Vicky crushing another pill, and Goody’s in the kitchen, looking in the freezer for my bottle of Everclear. It isn’t really a beverage, but a solvent I use for making hash-oil and Woodrose extracts.

“Got any clean glasses?” he yells.

“Ain’t likely,” I answer.

He comes in with a Styrofoam cup, left over from last spring’s seedling operation, and a jug of questionable OJ, starts mixing a rocket fuel screwdriver.

“Don’t waste that,” I say.

“Oh, we won’t waste it,” he says.

I indulge them both even though zero work is getting done. Keeping Vicky on my side is pretty key. She’s an expediter, a consistent mover, and I like the possibilities when she rolls into town. Besides, a pound of those shrooms she almost got nabbed with are slated for my racket, so she deserves leniency.

Things are always like this with Vicky. The deal always gets frenetic and edgy, but you learn to expect it with her. I started dealing with Vicky a couple years back, when we were still living in Staddlerville with Goody. It was late in the summer and we needed money for Gina’s Chem textbooks in a hurry. I put the word out on the scene, up here in party-town, that I had a small but pure quantity of the 5-MeO-DMT—the rarest and most delicate of synthetic, shamanic commodities. At the time, a gram of pure was worth a thousand dollars and broke down to at least two hundred religious orgasm-inducing doses.

Vicky was the only scenester crazy enough to show any interest, and, in reality, nobody else in town knew what the fuck a DMT was. When she heard the deal she was all about it. Said she would take whatever I’d come off of. She didn’t even flinch when I told her my stash was hidden away out in the creek-twisted bowels of Southern Jackson County. She was like, ‘Let’s go, I’ll drive, right now.’

That three-hour drive down to Bear Fork was like bonding for Vicky and me and Gina. The late-summer hills along the interstate turned a sort of orange in the tangent sunlight of the afternoon, and that day we jammed out the whole way to Kool Keith rapping pugilistic sci-fi rhymes in his alter ego persona—Dr. Octagon, the Black Elvis—Half shark/alligator, half man.

When we got to Bear Fork bottom we parked her car by the red dirt road and walked the right-of-way through a neighbor’s field. We rolled up our pant legs and crossed the creek with our shoes around our necks, then rebooted and hiked to the top of the impassable driveway.

When we got there I quickly dug out my stash: the pure crystalline DMT, the synthetic soma, the ambrosial Ayahuasca, the heady Yage potion of deep jungle lore and ritual; and somehow, half the known supply for the tri-state area was there in my palm, vacuum-sealed into a tiny, triangular aluminum envelope, still wrapped safely in the gray-market chem-lab packaging in which it came, marked clearly, unambiguously: Poisonous Non-consumable. I pulled out the big mirror, and a fresh razor blade as Vicky and Gina looked on. I cut a slit in the aluminum and poured the tiny translucent rocks, uncrushed, unadulterated into my porcelain mortar and mashed them to the thinnest possible dust. I poured it on the mirror and eyeballed the powder into symmetrical lines, then coaxed equal amounts into a dozen vegan gel-caps.

I put the caps in a little jar and handed it to Vicky, with slightly shaky hands. Looked like the most illicit thing I’d ever seen, and somehow, at the same time, the holiest.

“Remember,” I told her, as confidently as I could, “each one has twenty doses.”

After I doled it out there was a fine residue on the mirror and the razor, almost imperceptible, unweighable, what I imagine cosmic space dust to look like. I pointed to the off-white ripple and said, “What about this? It’s yours.”

Vicky squinted, leaned in to inspect it, said, “Let’s smoke it.”

The reaction was intrepid, wicked little smiles all around.

Moments later we were on the front porch of our old farmhouse; an elevated balcony of a thing with a hammock and rusted steel chairs, overlooking the holler. I’d dosed a joint with the stuff and it was impossible, really, to know exactly how much was in it, but I knew from experience that it would be just about perfect.

We each hit it once. First I lit it, inhaled and passed it to Gina, she puffed lightly then handed it to Vicky who, for the first time, would smell the acrid blue smoke, feel that heavy, disturbing taste on her lips. And the look on her face in that first heartbeat is one of those things etched like a stained glass tableau in my mind; as the spirit entered her blood, an orange and green hummingbird zirpped twice around her head, hovered for ten million years half an inch from her eyes, then disappeared. We all wanted to ask if it was real, but speaking during an astral launch, when your inner peace is rising like magma, bursting to come out, is implausible, and the words that erupt come cleaved and metamorphically fractured.

I looked at the girls. I knew they’d seen it too. We heard it, felt the palpitations of those invisible wings, sensed them on the raised pores of our forearms, on the alert hairs of our neck and spine. We perceived that totemic visitor like the immaterial guest at a séance, but that doesn’t mean it was real.

In the next breath, eons from the first, we became certain of what was real, and none of it had to do with hyperdimensional insect-birds, with porches and hollers, or Chemlab workbooks. Reality was unconcerned with Dr. Octagon’s Blue flowers…and oblique alphanumeric tryptamine nomenclature. Realness, at that moment, for Vicky and Gina and me, was a visceral intuition, an awareness of the slightest tantric tug as our souls undulated back to whichever darkmatter multiverse they came from.

Something in that gesture of coincidence suggested to me the existence of a spiritual imperative, the exact nature of which grows more illusive, and more important to me as the weeks and months and years accrue.

Days like those are scarce. They are precious and doomed.

After that trip to Jackson County I became firmly implanted in her circle, and she in mine. Since then, whenever Vicky has something to offer I get a whack at it, and anytime I have a harvest she’s on the distribution short-list. Most often it’s profitable on both sides, but neither of us mind doing a deal for next to nothing once in a while, just to keep the avenues open, to maintain the flow. She’ll get a good price on these trees, I’ll keep getting shroom pounds on front, and random weirdness for the head.

Vicky and Goody split the scrip-scag, then pass the rocketdriver back and forth, making contorted, tortured-monkey faces as they swallow. I’m surprised the Styrofoam doesn’t melt into napalm.

Vicky swings her head back and forth, shaking off the jolt. She coughs, then smiles at Goody. “Whoo!” she screams, eyes closed, leaning on Goody’s shoulder. Her flightiness, her undefined horniness, reminds me of Gina’s friend April, like a strawberry blonde April. She gets up, walks to the bathroom, listing to one side on her way down the hall.

She looks steadier when she returns from the bathroom.

“When’s your girl coming back?” she says.

“Bout two weeks, maybe two-and-a-half,” I say, holding up a Heavy Duty Fruity bud the size of John Holmes.

“Bet you miss her, huh?”

“Sure,” I say. “Yeah, I miss her.”

If she was here to see the house like this, though, I’d have to deal with some potent, loaded stares, irate, disappointed looks, silent, stressful pleas. I’m actually glad she’s not here for this. What haunts me most is not the thought of me getting hauled off to lockup, it’s the idea that I might drag Gina down with me. The thought of skinny, pale Gina getting booked and processed, waiting for bail with the hookers and crack-ho’s, makes me seriously question the operation. Any cheap-ass mistake, my hubris or laziness, a bad judgment call or inescapable dharma, some simple thing that I do could break her life, and if it did the only person she could call for help would be her mom. Maybe that’s my real nightmare: Gina’s mom rescuing her from me.

Goody mixes another one, swirls the cup with a flare, hands it to Vicky.

“Death from above,” he says.

“God save the queen,” she replies. She shoots it fast then whoops again, goes into paroxysms of ethanol shock. She slouches way back on the couch, takes a deep, chortling breath in through her nose, then says, “Maybe we should take our clothes off.” The words trail off like a sigh.

I shoot a quick glance at Goody. We both pretend not to hear that, both confident that our partnership has obvious limitations. I get up and carry some plants to the office, take my time hanging them.

Before long they’re pulling on jackets and hats and heading out to the Brew Pub in the middle of the blizzard. Vicky leaves her backpack and most of her dope in the kitchen, Goody leaves me with the trim pile in my lap.

I’m glad to see them dip, though. The whole time Vicky was here I kept peeking out the window, waiting for them Brown Bears to come out of hibernation, track her down to my doorstep. Some people attract that kind of heat, bring it down on themselves usually. I’m not sure if Goody was trying to skate on the work, or just get her out of the mix for a minute. Either way I’m left holding the bundle.

In the quiet void of their absence I notice the radio again, the crappy Vocalese jazz show now. I let it play because I’m about elbow deep in the gunja and I know the blues show comes on after this anyway. So I just wait it out.

I work as fast as I can on the pile but it seems like I’m going to run out of space in the office, and the bedroom. Can’t hang them in the basement cause they gotta stay dark and dry. Not really sure what to do with the rest. The floss lines are already stretched tighter than banjo strings, won’t hold much more. We never had this dilemna before, and it doesn’t bother me one bit.

I go into the bathroom to explore the possibilities. Try to calculate how many I can hang on the shower curtain, whether I can go two weeks without a bath if need be. In the mirror I see for the first time the hives creeping up my neck, the red check marks on my face from when I whacked myself. And the eye is definitely going to be an issue. I can’t find the bottle of Visine in the medicine cabinet, so I start washing my hands. Before the water warms up I hear the yawp from out back, a snow-soggy, whimpering yawp, but enough to jar me into action.

The phone rings as I dart into the living room, and exactly two nanoseconds later Salsa knocks on the door. He whistles a three note Miles Davis quote, a kind of speakeasy sign he uses with me, and other dealers on the scene, our equivalent of Shave and a Haircut.

I decide it’s no use to keep up the front, he’ll see it soon anyhow, and he’s gotta know already, so I open the door. He swings in with two inches of slush on his boots and a nasty white wind at his heels, covers my welcome mat in an instant. He drops his knapsack and pulls off his coat. There’s a cone-shaped spliffy hanging in his lips. It sags down to his chin when he takes in the scene on my floor, the Mylar tarp, the bare branches piled like skeletons in a mass grave. The ethylene smell of decaying chlorophyll hits his nose and he is caught with almost nothing coherent to say for some time. I lock the door and take his coat to the kitchen, the only weed-free zone in the house.

“Where’d this come from?”

“What the fuck you mean where?”

“I mean…” he stammers.

It occurs to me that he really doesn’t know. He hasn’t been playing dumb, he just has no attention span. Now he’s getting it. Like the girl who’s been cheated on, just figuring out the years of obvious clues.

“This is yours?”

“Half of it.”

After he takes his boots off I show him the office. I can see the line of his jaw gain definition as he clenches, still grinding the doob with his canines. He looks vaguely angry for a moment. His eyes wide, pissy.

“You should’ve told me.”

“Never tell anyone,” I say.

“Yeah, but I could’ve, you know, cooled it off some,” says Salsa.

“Whatever. If you didn’t know, then no one does, so it don’t really matter.”

“I wouldn’t have you sitting on all that shit if I’d known.”

“Bull,” I say.

He looks at me, and then at the rows of revolution, shakes his head with the slightest resigned, duped gesture.

“Come on,” I say. “If you’re gonna be here you might as well trim.”

We smoke his cone and work the harvest. Mostly I work and he plays around with the plants, dissecting them, fascinated like a sixth-grader with a bio-lab frog. He’s moved half a ton of the shit in his life and never seen what it really looks like. Funny, to me, how far most people are from the modes of production, even with commodities they make their living on.

I try to show him the right way to hold the stem to get the best angle on the leaves, but he only pretends to listen. Really he’s thinking about all the faith he’s had in this idea that my place was less risky than his. He’s been in two apartment busts in this town, so his paranoia is well founded. And Gina and I keep a low profile compared to a lot of these high-volume movers like Teddy Big-Timer, Mr. Seoul, and those cats. I can tell it’s rubbing him. He’s hurt, like Goody and I had a slumber party, didn’t invite him. Like I don’t trust him. He’s refactoring his business model. Maybe he’s wondering what else has been slipping through the cracks around him that he hasn’t picked up on, but I doubt he’s that introspective. He’s more emotive than cognitive when it comes to self-examination.

“Look,” I say. “Like this. You’re wasting so much time, just use the tip. Like this.”

I show him again how to do the trim, but he’s glass-eyed and seems to be sugar crashing. Hearing myself pester him makes me feel like an older sister, teaching him how to French-braid, or sneak cigs from Mom’s purse.

Finally, I give up.

“Want some orange juice?” I say.

“Hell yeah I do.”

Salsa hangs out while I try to clean up some, try to figure out what to do with the rest. Hate to think someone would have to drive this over to Goody’s place, smelling like a road kill skunk. I stash all the waste in the office, consolidate the pile. When I come across Salsa’s backpack sitting in a shallow mess of snowmelt, I hold it up and say, “Still need me to camp out?”

Salsa considers it. The scale of pros and cons has shifted dramatically in his mind. He squints while he thinks it over. So this is not the safehouse he thought it was, but that doesn’t change a thing about his fiancé’s attitude, plus he’s got no one else that wouldn’t pinch him blind if given the chance. I can see that he doesn’t like questioning his assumptions. Screws with his faith.

“Yeah,” he says. “Just tonight, though. I’ll figure something else out until you get this taken care of.”

“Sure,” I say.

The blues show comes on the college station and that picks our mood up. Salsa chugs pulpy chunks from the bottom of the OJ carton, then grabs my old acoustic. He retunes it by ear to the open tuning on the radio. Open C, I think. Sounds like Leadbelly or Blind Lemon Jefferson. He picks up my hand-blown oney and plays along, countering the bent melodies of the scratchy folkways recording with this uneven glass slide in his palm. It’s exceptionally hot, and it proves what they say about poor musicians blaming their instruments. To hear him play on my guitar, my strings, and make it sound like that, I start thinking of better excuses.

When Salsa holds an instrument in his hands, that’s the only time his eyes stop darting. He doesn’t watch his picking or his fingering, when he gets into it he goes autistic, locks his gaze on the foreground, in mid air, seems to read something written close on the ether, tapping into a stream of fluid musicality hiding just under the surface of this world, wholly invisible to me. It can be almost embarrassing to watch, to see him go defenseless like that, to see the pure, naked Salsa, when the banter dies and the persona dissolves into that resonant, rhythmic thrum.

The trance doesn’t last, though. The yawp is now a muffled yerp, but it is still distinctively nauseating. I stop Salsa’s playing and peep out the window. Pure whiteness, but I can hear Goody and Vicky coming loud as shit down the walkway. They’re stumbling, hillbilly drunk and junked-out, she’s hanging on him guffawing breathlessly as they make it to the porch. Salsa’s still quiet, his ears perked up suspiciously. I’m about to open the door for them, but I stop short and listen. They’re talking but I can’t make out what they’re saying. I smile at Salsa. It’s like listening at your parent’s keyhole. They get quiet then suddenly Vicky goes off wailing like a southern belle actress.

“Make love to me Goody. Make love to me now.” She sounds desperately serious and zoused. I look through the peephole and see her pulling him off the porch into the snow.

“Hold on, hold on, whoa,” says Goody. He’s buried now in the drift between my house and the next.

Now here’s something Gina would like to see, I think.

Vicky’s writhing beside him, wailing, somewhere between convulsion and hysterics. A sadness in the cry betrays her. I can tell by her tone that she’s high enough to see herself from the outside, smart enough to be freaked by what she’s seeing.

Goody staggers to his feet, pulls Vicky up from the demonic snow angel she’s embedded in. Her bleating fades as they make their way back to Goody’s truck and pull away. I look over at Salsa, still palming the glass pipe, legs crossed under my cheap-ass dreadnought. I’m not certain what he’s thinking, probably that Goody’s gonna go sleaze-out with that girl, leave his girlfriend sleeping alone in the blizzard, pregnant at home. If that’s what he’s thinking he’s not too far off.

“God save the queen,” I say.

Salsa nods, like he knows what I mean, then picks back up on another twelve-bar pentatonic groove, hitting harmonics on the twelfth fret, letting it buzz slightly as he slides down to the fifth.

Wes Trexler is an American writer and documentary filmmaker based out of New York City. His most recent stories have appeared in the Wisconsin Review and Willow Springs. Several others have appeared in the Rag Literary Review, including one which was awarded their fiction prize in 2015. Mr. Trexler is co-founder of the indie label Fish Ruler Records and is involved in various lost political causes. He studied at Eastern Washington University (under Samuel Ligon and Jess Walter) and attended the Squaw Valley Community of Writers workshop in 2005. He lives on a sailboat and plays clarinet.