Here goes the mother across the parking lot, insulated lunch bag packed with leftover Chinese, brain swirling with what to say at the ten o’clock meeting, the steps she must take to plug in and sync the projector in little enough time that her boss doesn’t scoff and call in a man. She thinks of the dinner she will make after work, tilapia with salad. She and her husband have determined to get healthy before their child is old enough to remember them any other way––they can’t get takeout so often. And she needs to better manage their time, too; if she did they would already be cooking. She’ll become a good example. After she gets the baby from daycare tonight they’ll pick up more produce at the supermarket. But first, the meeting, her first major client account since maternity leave. The mother pulls open the door to the building in which she works and goes inside, her lunch bag barely through the gap when the pneumatic door shuts.

* * *

She realizes thirty-six minutes later. She sprints down three flights of stairs, across the lobby that never seemed as long or as wide as it does now, into the parking lot where the baby lies in his car seat: heavy, limp, limpsweatydead, she knows before she even sees him.

Through the tinted window, his skin is the sickly shade of the Orbit she found melted in the laundry last week.

Soon the police arrive. They find her slumped in the backseat, door open, holding the dead baby to her chest. Her right hand supports the back of his neck. The officers look at her and don’t need to ask questions, but it’s their job. She tells them what they already know. We’ll have to file a report, they say. When the ambulance arrives soon after, a young paramedic takes the baby from her, looking at her in a mixture of what she will later, in the station awaiting interrogation, recognize as revulsion and pity. The police pull her wrists together and snap handcuffs around each one, tell her she has the right to remain silent. The ambulance doors close in on the baby. She shrieks again.

The father, silent, pays her bail. He will not speak on the drive home. Though they are not in the kill car, which has been taken to an undisclosed lot for processing, she feels claustrophobic, unable to breathe. Her husband will not speak. She cannot open her mouth or the car’s air supply will decrease all the more.

He goes to bed when they get home, and so does she. She watches as he turns his pale back to her.

Later that night the mother awakens, her bladder full to bursting, sick with the desire for release. On her return from the bathroom she hears a noise, like mewling, coming from the baby’s room. The baby? They own no pets. But their son is dead now. Dead.

Is it possible she dreamed today, that she’s taken sick and never actually went to work? The idea suggests itself like a woman in a red silk robe, leaning against a doorway. It doesn’t feel possible the baby is dead. No, Colin is dead, she tells herself. Killed. Your fault.

She has heard that asphyxiation feels like drowning, that smoke and water are not all that different.

The baby wails. This isn’t right, says her brain, this is crazy, but already that whisper of a thought is trailing off, her son’s voice taking over every part of her, transforming her into a vessel of solution, efficiency, need. The hallway outside the nursery smells like freesia and jasmine, flowers she could not recognize by sight. A nightlight with oil attachment has been plugged into a socket down by the baseboard, a blurry orange halo against the blue wall. Cornflower blue. Baby blue, like the onesies she and her husband were given before the baby was born. Her son cries for her.

I’m here, she tells him. I’m here. When she enters the room, the baby stands in his crib, one arm holding onto the rail and the other reaching out. It is a thing he has never done before and she feels a surge of pride in him, her precocious child that she birthed from the cavern beneath her belly, that he is strong enough and smart enough to pull himself up to stand, and so many months before the books say he can.

Hi, whatcha doin’? she says. The voice comes so easily to her; at its high, familiar pitch he smiles and claps and falls down. His face wilts into a red carnation, his cry filling her with a dense and inexplicable joy, until she crosses the room and picks him up.

Shhh. It’s okay. It’s okay. She strokes her son’s hair and he quiets. His face turns to her breast, clothed in an old T-shirt of the father’s. He hiccups. In the dimness his cheeks are as wet as a mermaid’s, purple and iridescent in their sweat like the rainbow fish of her childhood. Maybe he is sick. She feels the baby’s forehead. Hot, but to her it always feels too hot; the father says she overthinks things, worries too much, that they are raising a child, not running a nation. Her husband doesn’t understand the delicate fragility of nations. Do you have a fever? she asks the baby. He does not. What do you want? What can I get you? she asks. She has always spoken to him as if he is a guest in their home, a font of unknown and changeable desires.

He rubs his damp cheek against her breast again, puckers and widens his one-toothed mouth. That’s what you want! she exclaims. You’re hungry, you little monster! Babies have always seemed monstrous to her in this way, how they cling and suck life from their mother, and yet she adored that time, perversely enjoyed the initial pain when her nipples cracked; he had been learning.

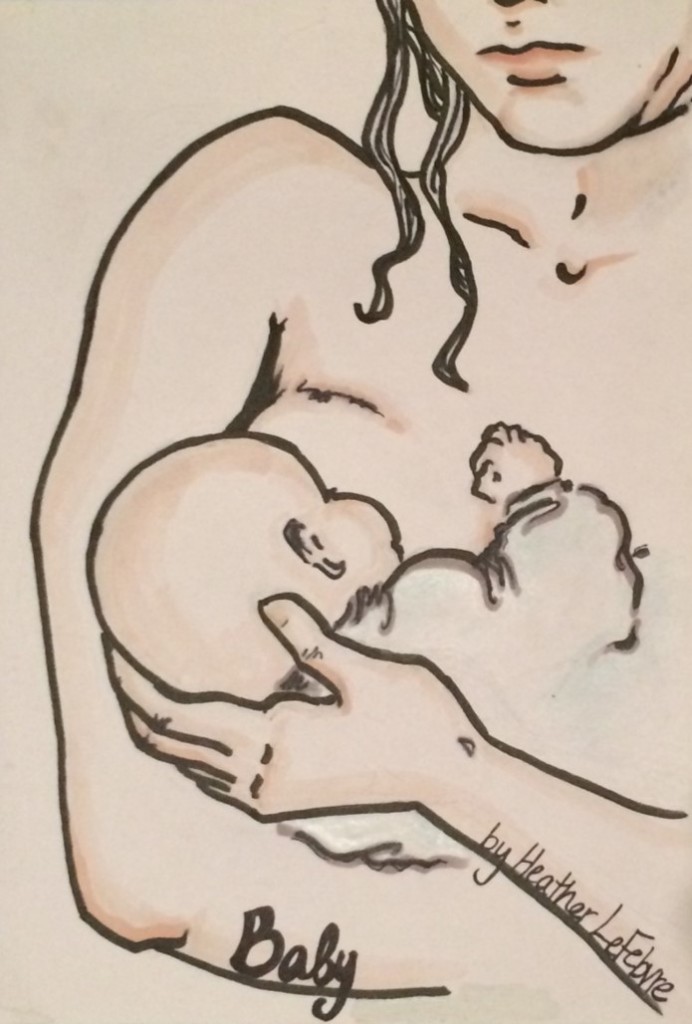

A sensation of doubt wriggles inside her brain––you shouldn’t be breastfeeding––but he’s too young to be weaned yet. Far too young. The baby presses his open mouth against her T-shirt more insistently now, drawing out the rise of her nipple and its milk, a stain forming an aureola on the cloth. She laughs. Hold your horses, she says, give me a second. Back into the crib he goes, off comes the shirt. The apartment’s central air brings goose bumps across her shoulders and down her arms. The baby latches with the urgency of one starved.

* * *

Closed casket. Hundreds of people show up to the church, mourning, gawking, crying not because they know her or her husband or her child but rather out of principle, because a baby has died, and since they have known their own babies they assume they know hers. Strangers, fat and wattled as birds.

She has not slept in three nights.

Next to her, her own mother squeezes her hand, pours great tears into a ragged tissue. It feels easier to sit in this pew, in this dress, when there is someone else to comfort. Doing so keeps away the panic that the baby will be gone from his crib tonight, that he is truly gone forever.

His little mottled face swims in her brain, shimmering in the heat. She could have sworn she dropped the baby at daycare that morning––why didn’t she? How couldn’t she? What could possibly make her forget? Always, in the daytime, the mother sees his face as it was in the car. She has to tell herself that the funeral, the police interrogation, is only half the story—that tonight the baby will be safe at home, waiting for her. Her throat swells.

Her husband delivers the eulogy, his face tight and red. She focuses on the familiar scent of incense and holds a handkerchief pressed to her lips. If she opens her mouth she will tell them about the baby and with her words he will go away again, just-like-that! He came back for her alone.

Strangers watch the great, dry net of kerchief. I would be a wreck, they whisper. But the mother does not appear to be a wreck. They all know what that means.

That night the baby’s skin rubs dry against her knuckle, dirty even, like a canvas sneaker left in the braided cavity beneath a porch. He hasn’t felt that way before, and he’s a little cold too. This isn’t right, she thinks. This isn’t the deal––he should be getting better, more like his old self, not worse. Even as a secret mother, she fails.

You wanna blankie? she asks. Let me get you a blankie. I’ll be right back.

Blankets and towels are kept in the hall closet. She remembers a factoid she read in a magazine once: that if you’re stricken with hypothermia you should take off all your clothes and huddle in a sleeping bag. Just hold someone, or yourself, to get warm. She thinks of wolves huddling together in burrows of snow. The afghan drags between her legs onto the floor.

From the doorway the mother looks at her cub, her naked wolfling. He has not yet cried tonight, but she knows from experience that this means little. Or perhaps this silence means everything, connects to the cold, papery finish of his cheeks and stubby fingers, means he’s done crying for good. Or he’s punishing her. She places the afghan on the rocking chair and removes her pajamas. The baby rolls awkwardly onto his side to watch her. In the glow of his sleepytime sheep lamp the whites of his eyes shine as round as skulls, or marbles. He fidgets when her breasts are exposed, his little fat hands grabbing at each other and slapping one another down.

C’mere, bug, she says.

Under the afghan she holds him to her, rubs his back. Her open hand touches both his shoulder blades at once, and she startles at the texture of the skin between, grainy, almost like sand. He lets out little hiccups of joy. There, there, she says. An illustration of a woman rocking her child to sleep, a book her mother once gave her, pops into her mind. She smooths the hair curling behind the baby’s ear. As long as I’m living, she whispers, my baby you’ll be.

Her husband frowns as she walks in from the shower the next morning, stops getting dressed. What’s that? he says.

What’s what? she says. But she knows exactly. She turns away from him to face the bureau.

Your tits, he says. Turn around. What the hell is that? Looked like blood.

She will not face him. I got a blister, that’s all.

That’s all. How the—

Gloria took me tanning, she says. Stupid; he’ll see right through it.

Since when do you go tanning?

Since my fucking nipple blistered, she says.

The mallet of his thoughts swings heavy in the small room. It’s their longest conversation in days. Finally her husband says, They look enormous.

She hooks herself into the bra she’s taken from the bureau and at its touch her breast feels on fire. Is this how the inside of the car felt, on the day she forgot their son? Flames? Or a sensation of baking, a contained heat, like tanning beneath an artificial sun? She’s lucky he gave her a second chance.

At the thought of the baby, the milk moves. She can feel beginnings of dampness between her skin and the bra. If she turns around her husband will know he’s back. He’ll take her son away; he’ll send her to the loony bin.

With one hand over her mouth, the other limp on a drawer pull, she begins to cry.

Footsteps come closer. His hand falls on her shoulder. Honey, he says. You can talk to me.

That’s just what he wants, to find out! Don’t touch me, she says. Her voice has thickened too much to form the words. He keeps his hand there, moves closer so she feels the gentle swell of his body behind her.

Hon, he says.

Go to work!

Later in the week she catches the father emerging from the baby’s room, a sippy cup in his fist: the candy cane one they bought for the baby’s first Christmas.

What are you doing? she says. So he does know! He must know how the baby has dried out, how she wets the baby’s skin each night after bed. He’s been looking for clues.

Found this little guy in the crib, he says.

She must have left the cup there the other night, after washing. She puts her hand to the back of her neck.

That’s summer for you!

She doesn’t understand. Isn’t he angry that she’s hiding their son? The father holds the cup by its translucent white lid to show her the peculiar shadow inside.

As he walks past her she asks, Where are you going?

The mother, terrified, follows her husband through their apartment onto the balcony, watches from behind as he unscrews the sippy cup with great tenderness. Fuck, he says. He holds the cup far out over the lawn and shakes. A sand scorpion, long as a pinky, falls into the grass.

* * *

Charges have been brought. Protestors swarm the courthouse.

At the hearing, as her lawyer has requested, the mother keeps silent. Thinking of the night before, she has to remember to look regretful. She calculates how long it will be before she can see her son again: ten hours, nine hours. Behind her in the pew, her parents cry loud, desperate sobs.

The judge watches her eyes watch the clock.

* * *

The baby feels scaly. Water has made his skin worse.

What’s wrong? Whassa matta? she coos. She’s running out of moisturizer for him. He claws at her breasts in pantomime of a tantrum. It’s okay, it’s okay. Don’t you worry, little monster. She pulls her arm out of the strap of her shirt, freeing her breast. I’m here for you.

The baby sucks and sucks and sucks.

In the morning her husband says, That’s not normal.

Says the man, she answers. She finishes applying deodorant and puts her shirt on.

It’s not funny. A doctor needs to look at that.

Have you seen Dr. Yakarian about your blood pressure yet, like I told you?

Ellen, he says. You need to see someone.

While the baby feeds, she hears a creak. She turns her head to see her husband in the nursery doorway, naked but for navy boxers. Panicked, the mother clutches her son closer. He gurgles against the plug of her skin. She can feel the baby’s single tooth, smooth as eroding seaglass, jut into her flesh.

You’re up late, the father says. He steps into the room, one foot closer to her rocking chair.

You get the fuck away from me.

The baby makes a noise, muffled, its throat filling with milk.

I had to piss, and I saw the light on, her husband says. He looks them over, head to toe. His eyes linger on the back of the baby’s head, on her bare skin. You shouldn’t be in here. He takes three more steps.

Don’t you touch him! she shrieks. The baby’s tooth will give her a bruise. The baby gurgles again, softer this time.

She presses her child tighter to her body, so close she can feel her own heartbeat in her breast.

The husband says her name, says it again, keeps saying it.

I’m not crazy, she says.

Her husband puts a hand against the side of his nose and rubs up and down. Come to bed, he says. We’ll talk about this in the morning.

Don’t look at me like that! she shouts. I’m a good mother! And, noiselessly, the baby’s mouth falls slack.