Jonathan Chudler

After her husband had disappeared with someone younger and “shaped less like a refrigerator,” Judith took on boarders. She insisted that the boarders neither drink, nor have relations between them, nor have overnight visitors of the opposite sex. This was not that kind of house, she would say. This was her home, a place with a dignified history.

Despite the boarders’ company, Judith’s loneliness had settled over the house like a sheet over abandoned furniture. Her grown son’s old room in the attic was still filled with the fetish items of boyhood idyll: a kite rolled up in the corner of the closet; bed sheets decorated with hypermasculine superheroes; a ribbon for a second place finish in the Pinewood Derby, the small wooden car still sitting out on the dresser.

Judith’s ex-husband had for a while been the honorary consul of one of those countries created after the collapse of the Soviet Union. “It didn’t mean much,” she told Samuel, a prospective boarder. “They wanted consulates wherever they could have them, for legitimacy, I suppose, as a new country. Well, new and old, of course.”

“Is the house still a consulate?” Samuel asked.

“No. We never did much in that regard. Just flew the flag, really. We helped people when we could, of course – traffic tickets, passport trouble. It did become a sort of refuge. People still find their way here, from time to time, still think I’m here to help.”

The attic window overlooked the shingled rooftops of shorter houses, and traffic flashed between them.

“After my husband left and our children moved out on their own, the house stayed with me, and I with it. At the moment I can offer only the attic.”

•••

These were the closing years of the twentieth century, a time between histories, when we had no villains. In cities shinier than Detroit, young people like Samuel got rich developing technologies to make the future more perfect. Samuel had built websites in Manhattan before he cashed in his stock options, vanished, and then reappeared in his hometown near Detroit. He announced his arrival to no one there who might care, but instead moved into Judith’s attic, hoping to avoid any entanglements.

Another boarder, Richard, was quite a bit older than Samuel. Richard’s shelf in the refrigerator was tidy, its neatly sealed containers often holding various forms of venison he had hunted and butchered himself: ground for pasta sauce, flattened into patties, wrapped into sausage. He would say that he hadn’t bought meat at a grocery store in years. “This stew, in fact, is from a doe that was in the wrong place at the wrong time last November.”

Richard performed small chores for Judith, like dealing with the plumbing behind the ground floor bathroom that the boarders shared. Samuel didn’t notice that Richard’s tinkering changed the noisy way the flushing toilet sent a shudder through the walls, but Judith beamed. “Richard,” she said, “is always so helpful. I feel like he’s truly a part of this household, rather than just paying his rent.” Samuel inferred the contrast with his own general uselessness. “I feel so much safer with Richard here,” she went on. “After all, I would never keep a gun myself, but you can’t tell a man like Richard not to keep one, I’m quite certain.”

The last boarder, Asta, spent most of her time in her room with the door closed. When she spoke, Samuel noticed her accent and asked where she was from. Asta said, “Nowhere. I am from nowhere and everywhere, I have lived so many places.”

Asta had a face that strangers recognized instantly before realizing it was because they’d seen faces just like it in fashion magazines and on billboards. Despite this, Asta told Samuel that she was always changing how she looked. “My face, my hair, I cannot help it. I look in the mirror and say, ‘You look terrible’ and I know I must change something.”

“C’mon,” Samuel said. “You must know that you’re beautiful.”

“You are a sweet man,” she said, “but no, it is not true. I am a witch.”

•••

Samuel and Asta were in the kitchen together one night when his phone rang. He took the call in the hallway and then returned to the kitchen, where Judith admonished him for not eating enough. “There will be no illicit drug use in my home,” she said, “and your lack of appetite concerns me.”

Samuel denied the accusation, but still retrieved a yogurt from the fridge. “I do not understand Judith,” Asta said. “I often do not feel like eating. Sometimes I think that I might never eat again.”

Samuel suggested that rather than eating, they go out together to have a drink. After pushing her food back and forth across her plate, Asta said, “Why not? Yes, let’s do this.”

Richard entered the kitchen with a haze of leathery sweet smoke, his pipe still in hand, and glanced at Asta as she took her plate to the sink. He winked at Samuel and then continued to his room.

They chose Olive, a bar decorated with faded tapestries and mannequins wearing tunics, like kings and queens on the black and white chessboard floor. Samuel bought a cigar and pretended he knew how to smoke it. Asta refused to try it but smiled at Samuel’s awkward attempts; after his second drink, he started to believe that she was genuinely impressed. After their third round, they found themselves very far away together.

“So, what brought you here, from wherever you’re from?” Samuel asked.

Asta rested her elbow on the top of their booth, her head resting in her hand. “So many reasons,” she said. “So many and none at all.”

“What does that mean?”

“I am still learning English, and I cannot always find the right words.”

“I have a hunch that your English is just fine.”

“Of course, you are naturally suspicious. It is not your fault. You are just American.”

Samuel asked what she was doing now.

“Now? Now, I am hiding with you.” She smiled and raised her eyebrows for a moment, and he felt that they were, indeed, conspiring together. Against what, he couldn’t guess.

The moment passed. “I’m not hiding,” Samuel said.

“No?”

“No.”

Asta touched Samuel’s arm, then held it as she leaned toward him. “Who calls you, then?” she said.

“When?”

“The calls that you receive, like the one you had tonight.”

“Could be a few people, I guess.”

“No, Samuel. It is the same person, I can tell. A woman, yes?”

“My sister,” he said. “You must mean my sister.”

“Your sister? What is her name?”

Samuel offered the woman’s real name – Katherine – to avoid confusion should Asta ask about her again, as he hoped she might.

“Tell me about her,” Asta said.

“Well, she lives in San Francisco.” True. “She’s married.” Also true.

“She wants me to move out there with her.” Possibly true. Katherine said this, but couldn’t mean it.

“I’ve heard it is a lovely city,” Asta said.

“Yeah, it is. It’s still booming, too.”

“Then why stay here, if you can go to such a place?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “Maybe I like being where nothing’s happening. It’s mostly why I came back here in the first place.”

“You’re strange,” Asta said. “You know this?”

Asta would have thought Samuel stranger still if he’d told her the truth: Katherine was not his sister, but rather a woman in New York with whom he’d carried on an affair while her husband maintained their home in San Francisco. After he’d quit his job, but before returning to Detroit, Samuel stayed in Katherine’s high rise corporate apartment in Manhattan. Now, she beckoned him to move out to San Francisco. She said that she’d hide him in her basement until he could find his own place.

“Yeah, I suppose I’m strange,” he said to Asta.

“You shouldn’t take me so seriously,” Asta said. “You really shouldn’t listen to a word I say.”

As they walked back to the house, Samuel put his arm around Asta. “This is not something we should do,” she whispered, but surrendered herself to the crook of his arm anyway.

Back at the house, however, Asta said good night and climbed to her room without looking back and without invitation. Samuel strained to hear Asta’s shoes as she tossed them to the floor above him. He listened for sounds that he knew he could not hear: the buttons of her blouse slipping loose, the clasps of her bra releasing one another, her feet stepping out of her slacks. Still and alone, he heard his own breath and the steady hum of appliances. The house was as quiet as it could hope to be.

•••

The next night, Asta came to visit him in the attic. “I thought it would be nice,” she said, “to have some tea.” They sipped their tea in silence. Samuel sat on his bed, and Asta sat on the floor, cross-legged, before placing her tea on his desk and moving to her hands and knees.

“This is Table Pose,” she said. “The yoga class I used to take always started here.”

She lifted her head while pushing her stomach down. She then arched her back and tucked her head, then again. “What’s that?” Samuel asked.

“Cat/cow.”

“Why are you doing this?”

“Why not? I need to stretch, and we’re not talking, anyway.”

“You’re teasing me,” he said.

“Teasing you? How?”

“Please, Asta. I have no idea what you’re thinking.”

She stopped stretching and sat up again. “This is not so unusual,” she said. “You are a man, of course you cannot know my thoughts.”

“Why not just tell me?”

“Tell you what? I have no thoughts to tell you. You are imagining something.” She lay back and lifted her feet straight into the air before dropping them behind her head, touching her toes to the floor. “This is plow pose.”

“I have imagined some things about you, sure,” Samuel said.

“Such as?”

“Well,” he said, “I’ve imagined you moving away from here with me.”

“You are a little bit crazy, yes?”

“A bit, probably.”

“I am not surprised,” she said. “I always make trouble with men. I cannot help it.”

“What do you mean you can’t help it?” he said. “Of course you can.”

“No, I cannot. It just happens to me.”

“Is that why you’re here, in this house?”

“Why are you here?” she said.

“Me? I like the neighborhood. The bars are a reasonable stumbling distance away. You’re the one with secrets.”

“Mr. America, Mr. Practical. Why you do you stay here when you can move in with your sister in San Francisco? Detroit is so ugly,” she said.

“It’s not that bad, really. You just have to squint.”

“Squint?”

“Yes, like this.”

“Ah, yes, squint,” she said. “I do know this word. You look at me like this all the time.”

“I do?”

“Yes, I believe you do it when you think I am crazy.”

When she said this, Samuel squinted at her – “Yes, just like that!” – but not because he thought she was crazy. Instead, he couldn’t believe that she was there with him at all. “See, right now, you think I am crazy,” she said.

“Yeah, I guess I do.”

“But I am not crazy,” she said, turning serious. “You are crazy.”

“Me?”

“Yes, you. For staying in this place, when you can move to a city like San Francisco. It is so easy for you, you can go anywhere you want. You don’t understand my life. You don’t understand other people at all.”

“Would you move there with me, then?”

“You don’t mean this,” she said.

“What if I do?”

“You don’t understand anything.”

She returned to her tea, drinking what was left in little gulps.

“Tell me,” Samuel said. “When will you leave this house? You won’t stay here forever.”

“No? Why wouldn’t I?”

“You just won’t.” Women like you, he wanted to say, don’t stay in one place for long.

“You’re the one who talks of moving to San Francisco,” she said. “When are you leaving?”

“I don’t know,” Samuel said. “Maybe tomorrow. Maybe I’ll just disappear.”

“Wouldn’t that be nice?” Asta said. “Wouldn’t it be nice to disappear?”

“I suppose it would,” he said.

Asta said that it was time for her to return to her room for the night. Samuel stood up and reached the door before she did.

“You’re really hiding, aren’t you?” he said. “You don’t leave the house during the day.”

“How do you know? Are you spying on me?”

“No,” he said. “I’m not spying. Just noticing things.”

“Let me go. Let me go back to my room”

“Only after you tell me why you’re hiding.”

“No,” she said, holding back tears. “I must go.”

“Tell me.”

“I am hiding from you,” she said. “Right here, in the same house.”

He lowered his arm from the doorway and stepped aside. “Good night,” Asta said, and pretended to smile as she walked past him and down the stairs. The steps creaked beneath her feet, all the way down to her room. If anyone else in the house was awake, they would certainly hear it, too. Samuel was certain that Judith lay awake at night listening for just such noises.

•••

Katherine described her home as tall and narrow, in a neighborhood still being reclaimed from San Francisco’s drug and sex peddlers; there were just enough jagged edges, she told Samuel, to remind him of Detroit. She would hide him in the basement, Katherine said. Her husband would never know.

Katherine’s basement sounded fine – carpeted, a couch, a television, and a bathroom that no one ever used – but Samuel envisioned himself above the city with the spires of Grace Cathedral. He saw Asta in San Francisco with him, a woman made out of toothpicks and glue, playing with her hair and waiting for him to come to bed. He didn’t dream a future with the Asta he knew – critical, dismissive, her fingernails bitten to nubs – but the Asta he desired. This Asta was a shadow, but warm, and without secrets.

He’s with Asta in their room high above San Francisco, where he sits by the window and drinks something warm and numbing – red wine, or whiskey. Outside, lights rise and fall in petrified waves on the city’s hills.

Asta lies behind him on their bed and hums a tune. “Do you know this song?” she asks, and hums a few more bars. “I cannot stop this song in my head, but I don’t remember the name.”

“It sounds familiar,” he says, “but I can’t place it.”

“It is making me crazy.”

None of this would work in a basement, where he would have to face Asta, and would have to help her identify that song. She wouldn’t float nude and perfect over a city indifferent to their lives, but instead would sit upright on the bed, legs crossed in cotton sweatpants, flipping the pointless pages of a gossip magazine. Samuel would know exactly what song she was humming, and he would hate it.

•••

Another night at Olive and Asta told Samuel that she had a secret to share with him. “I heard you masturbating after the first night that we came here,” she said.

“You did?” Samuel said. “I don’t think so.”

“Please, Samuel. Don’t deny it. It is natural, of course. We had been out together like we are now, and when I was in bed later I could hear you. Your bed moves a little. You must not notice.”

“And?”

“And?” she said.

“Assuming you’re right, why are you telling me this?”

“We are having drinks,” she said. “I am making conversation.”

“I don’t know how to respond.”

Asta leaned forward and smiled. “Tell me what you were thinking about.”

“I’m sorry?”

“Your thoughts, of course. Your thoughts that night. I am simply curious.”

“You’ve never talked like this,” Samuel said.

“How am I talking?”

“Sexually.”

“Please, Samuel. This is hardly sexual. It is just about your thoughts.”

“Listen, Asta, you must know. I was probably thinking about you.”

Asta tsked, and said, “Judith would not be happy if she knew you were thinking such thoughts in her house.”

“Judith is already unhappy.”

“And me?” Asta said. “Should I be flattered? That you thought of me like this?”

“You knew my answer before you asked,” he said. “It’s up to you if you want to be flattered.”

She sat back and shook her head. “You are just a man. It is just sex. It means nothing. It could be me or a thousand other women.”

“And what did you think?” Samuel asked. “When you heard me. What did you think about?”

“Think? I thought nothing. I just listened to you, did the same, and went to sleep.”

“Did the same?”

“Yes, of course,” she said. “You should not be flattered. You are just a man.”

As Samuel tried to fall asleep that night, alone again, he noticed his bed creaking each time he turned or shifted. He considered masturbating, to send Asta an invitation, but couldn’t do it while, as he assumed, she was listening and would expect him to do so. He wanted very much to disappoint her.

Samuel slid down, pressed his ear to the wooden floor, and listened. He heard faint gasps, but as he drifted off, he couldn’t tell whether the gasps came from Asta below him or from within his own mind. Real or imagined, it didn’t matter: they’d essentially had sex, separated only by a floor, a staircase, two doors, and the parochial whims of Judith.

•••

The next day, they shared the kitchen occasionally but didn’t speak. Daylight silenced him in Asta’s presence, but by dusk his head was filled with the perfect words he could say to her. Through his small window he watched the sky as it faded from grey to black, and several times jerked his head at what he thought were her footsteps on the stairs to the attic or, at least once, her knocking on his door.

As the night drew on, he imagined her lying in bed waiting for him, assuming that she had said enough and that he should come to her. He listened to the murmur from late night traffic until he was certain that the house was silent, and then stepped lightly down the stairs from the attic. I was hoping you would like some tea, he’d say, or we could just sit in the dark and breathe together.

Despite the hour, he could make out a dim light escaping under Asta’s door into the hallway. He couldn’t knock, the house as quiet as it was, but at least he knew she was awake. He turned the doorknob and held it as he pushed the door open.

The lamp on Asta’s nightstand cast the room in bronze. Barely illuminated, in Asta’s bed, was the unmistakable back of Richard. Asta’s bare, thin legs leaked out from beneath Richard’s heaving mass and, like talons, her fingers dug into the mattress. Samuel lost his grip on the doorknob, and the metallic sound of it snapping back into place elicited only a confused grunt from Richard. Samuel ran back up to the attic, two steps at a time, and slammed the door behind him. He spent the next several hours waiting for Richard to follow, the barrel of his hunting rifle leading the way. Samuel propped his desk chair under the doorknob as he’d seen done in movies, but he knew it wouldn’t stop Richard if he was determined to enter.

Richard never came. By morning, Samuel understood that Richard had no reason to hunt him. He and Asta would have just continued on after the interruption, undisturbed, as if a family dog had wandered in and out of the room.

•••

Samuel stayed in the attic all day and another night passed before he removed the chair from the door and went downstairs. Asta’s door was open and the light off, but he had no temptation to enter. He found Judith and Richard sitting together at the kitchen table, each with a glass of red wine, even though it was early afternoon. They both glanced at him as he opened the refrigerator.

“She’s gone,” Judith said just as Samuel noticed that Asta’s shelf in the fridge was empty. “She moved out quite suddenly, in fact. I suspect that something happened between the two of you that I would just as soon know nothing about.”

Richard finished his wine in a quick gulp and stood up, leaving his glass on the table. He winked at Samuel and left the kitchen. Judith told Samuel that he could have Asta’s room if he was tired of the attic. He declined.

“This wine is left over from the last party my husband and I hosted. We were honoring a surgeon who had defected in the bad old days. His medical credentials were worthless here, of course, and he sold expensive European pens at the mall. He joked that his pens, just like his surgical tools, were precision instruments. Toward the end of the dinner he started repeating, ‘Precision instruments’ over and over. ‘Precision instruments!’ Quite loudly. Everyone left, of course. It was the first time we had leftover bottles, and the last party we had. Now, would you like a glass?”

She filled Richard’s empty glass and, before Samuel could answer, handed it to him.

•••

Katherine suggested that, instead of moving to San Francisco, Samuel return to New York. She arranged an interview there for him with her company, in the World Trade Center, a few blocks from her corporate apartment. She’d left the key with the doorman, who would certainly remember Samuel, she said. It would be like he’d never left.

“You realize this would put me further away from you?” Samuel said.

“Only on a map. In every other sense San Francisco is closer to New York than it is to Detroit. What excuse would I ever have to come to Detroit? If you’re in New York, I could be there any time.”

She was right. Detroit is the reverse of a mirage: it appears to be a desert of despair in a world filled with palm trees and dates.

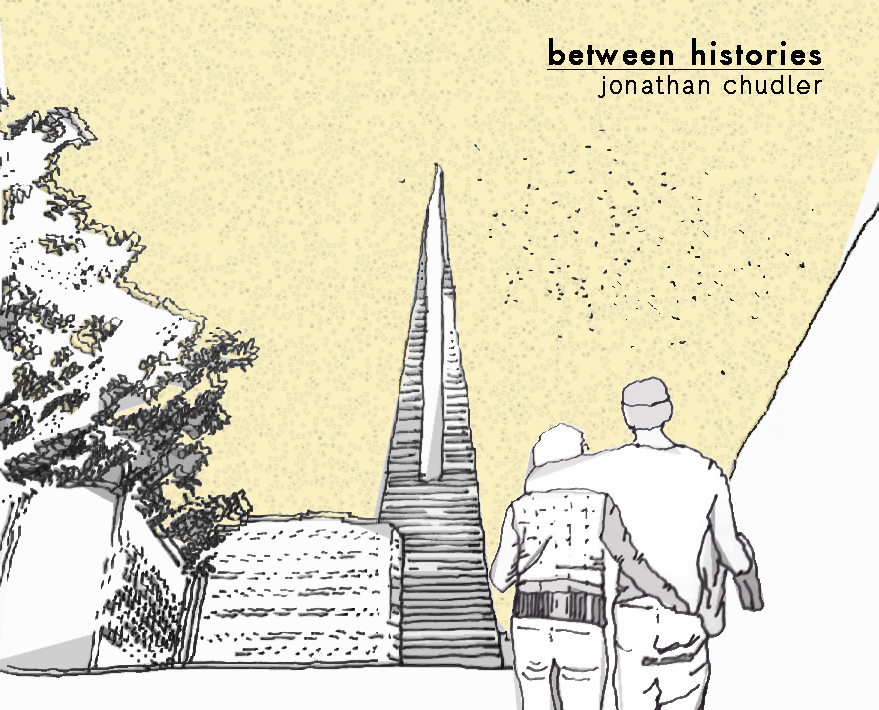

Despite his impending return to New York, Samuel continued to remember a life in San Francisco, a life he’d never lived, with Asta, a cloud taking the shape of a woman. In this life, Samuel and Asta walk together through a park, his arm around her, his hand on her hip. Distant hills disappear beneath a soft avalanche of fog. Asta suggests they have tea, and Samuel notices the clatter and steam of a café at the park’s edge. They approach the café – door propped open, faceless figures sitting at sidewalk tables – but they never reach it.

Since winning an award or two for his writing many years ago, Jonathan Chudler has continued to scribble away while focusing on law, business, and family. He is happily kicking off his forties with his first publications. His work was recently published online at Tin House: The Open Bar, and he is working on a collection of short stories.