The first night I did stand-up, I stood in a line outside the Houston Laff Stop’s entrance and signed my name onto a yellow legal pad. Now I was less than three minutes from going up. Lanky and 18 years old, I stood in a dark corner about 15 feet from the stage, a semi-circle clearly built to contain one person. A collage of white, purple, and orange lights shined on the performing comic, Russell, as he let loose. With his porcine gut, greasy blonde hair, and oddball driving cap, he looked like a coffee-shop version of Sam Kinison.

“You ever notice those crucifixes on the side of the road?” he said. “The ones with the little wreaths around them? You know what those memorials make me think?”

The crowd sat silent with attention.

“They make me think that Jews must be really good drivers.”

The laughter came in spurts as people dwelled on the punchline. Russell smirked like a five-year-old.

This was the comedy club’s Wednesday open mic, a carousel of amateur and semi-professional comedians. The format, imposed by the club’s balding manager, Dave, was simple: 25 comics, three minutes a set, no emcee. Dave was so militant about the three-minute rule that onstage he kept a three-foot-long digital timer facing the audience. Each comic would reset it with a remote.

I enjoyed Russell’s material, but I became increasingly nervous: the more he killed, the more I had to as well. My chest tightened and throbbed as I saw the timer hit 3:00. Inside my jeans, a bead of sweat dripped down the back of my right thigh.

“That’s my time,” Russell said.

After the claps ended, he pulled an index card from his back pocket and said, “I would like to welcome your next comic to the stage. Make some noise for Edward Garza!”

Russell didn’t actually know me. Per Dave’s instructions, we’d scribble the next comic’s name and introduce him or her. There were sporadic claps. I walked up four steps and onto the stage, shaking Russell’s hand somewhere along the way. The warm stage-lights hung in front of my eyes, forcing me to tilt my head down a bit. I awkwardly grabbed the remote from the nearby stool and hit the “Reset” button. I pulled the mic from the stand, placing the latter behind me. There were about 75 people in the audience. I held the mic against my chest with both hands, as if I were climbing a rope.

Too nervous to start my material, I said, “Keep it going for all the comics you’ve seen so far,” to which the crowd vigorously applauded.

It’s common for a comedian to begin a set with some self-reflexive comment, such as pointing out his or her celebrity doppelganger(s). The template often goes, “I know what you’re thinking: did (insert celebrity A) fuck (insert celebrity B)?” Since I didn’t have any proven stuff, I decided to open with such a joke. But I did away with the template, saying, “Ever have one of those days when someone asks you if you’re that guy from Slumdog Millionaire?”

The laughs built on one another until they formed something respectable. I’ll keep that one, I thought. The joke guaranteed that I wouldn’t bomb entirely. Still, for the next minute I received only lukewarm chuckles that reeked of “That’s clever, but it’s not funny.” One of my other jokes went, “I read that Eskimos now want to be called ‘Inuits.’ I like Eskimos, but I can’t support that decision. Who would want to eat an ‘Inuit Pie’?” I heard only beer glasses clinking.

Comics will tell you that, while it’s a scalp-snapping rush to deliver a successful joke, silence is indescribably excruciating, debilitating, and numbing. But if a comic says nine bad jokes and one funny one, he or she will cling to that funny joke like it’s a life-raft. To hear 50, 70, or 100 people laugh at words you once scribbled into a notebook is more than ecstasy. Like other artists, comedians seek approval, and they can receive it instantly.

“Whenever I go on a date,” I said, “I try to be a gentleman, even though I don’t understand all the rules of chivalry. For example, there’s the rule that says, whenever a man and a woman are walking the sidewalk, the man should walk closer to the curb. Because of course, if a Hummer H2 loses control and comes barreling toward my date and me, it would immediately be stopped—by this body.”

At this point, I opened my arms to display myself. After I said “this body,” the laughs came. Squeaky laughs, nasal laughs, laughs with the cadence of an automatic firearm.

Now for the closer. While I hadn’t tested such a joke, I knew it would involve my father.

“This story tells you something about my Dad,” I said. “When I was five, he dragged me with him to his check-up at the doctor’s office. While he took his tests I waited for him in the lobby. When he finally came out, a nurse followed him with a small line graph. She tapped him on the shoulder and said, ‘Mr. Garza, I just wanted to explain this graph to you.’ She pointed to one of the lower lines. ‘Your test shows that you have a hard time hearing speech below this decibel level.’ Without missing a beat, my Dad said, ‘That’s all right. That’s the level where nagging women talk.’ The nurse said, ‘Mr. Garza, this isn’t funny.’ My Dad said, ‘What?’”

My first show. Done. I reached into my front pocket for the napkin bearing the next comedian’s name. It was clearly a pseudonym.

“That’s it for me,” I said a little too quickly. “Now please welcome to the stage H. Darius Hilarious!”

Up walked a bald, sweaty man in a wrinkled black t-shirt. I waited at the mic-stand, shook his moist hand, and then walked to the back of the showroom, taking a seat at one of the small, elevated tables. I noticed a group of comics, all males, sitting nearby. Each nursed either a Budweiser or a Shiner. Russell was among their ranks. I thought about walking over and saying, “Good set,” but I felt I would come off more as a fan than a peer, whom I ultimately wanted to be. Maybe after a few more open mics, I thought. Maybe not.

Drained yet exhilarated, I stayed for five unremarkable sets, then walked out of the showroom—a cheese-ball lounge that looked exactly how you think it looked, red stage-curtain and all—and reentered the lobby. It was a grim blue color and smelled like old shrink-wrap. I opened the glass door and walked into a muggy August night. Mosquitoes darted under the club’s entrance lamps. As I drove home, I spotted a crescent moon above the city’s skyline, hanging as if transposed from a Tonight Show clip.

* * *

I hadn’t told anyone about that night. If I bombed, I didn’t want friends or family to witness it. The next morning I woke up, prepared a bowl of Corn Flakes, told my father to have a good day, and drove to Talento Bilingüe de Houston, a cultural arts center where I was interning. When I eventually told my family and friends what I’d done, they were beyond surprised. Why was the quiet, angelic Edward doing stand-up comedy? From what life experiences could an 18-year-old draw material? While always encouraging, my father even said, “What inspired you to do that?”

These were valid questions. I still cannot answer them with assurity. What is it, after all, that drives someone to get up in front of strangers and tell jokes? In my case, I relished the chance to have my opinions, my interpretations of life, recognized. I had just graduated from a high school of more than 3,000 students, a place where, as an honors kid who ran cross country, I felt like a member of a subculture. This wasn’t a terrible thing; I enjoyed the sense of community. But I always disliked the anonymity of a large school where you could truly know only a handful of people. Stand-up may seem like a misguided solution, but it appeared that comics spoke with substance about an otherwise faceless daily life. My comedy role models—Patton Oswalt, Mitch Hedberg, Louis CK—illuminated mundane events, offering a frame through which to view the world. Their crowds would laugh as if to say, “Things actually are like that.” As someone who was enrolling at the 35,000-student University of Houston—in America’s fourth largest city, no less—I yearned to create art with that type of intimate connection, however fleeting it might be.

And, hell, I wanted approval. While my parents and friends supported me, I felt untethered from society at large, but at home within a comedy club. And what signifies approval more than a room of people laughing and clapping in support of your words?

I also liked that, as in cross country, my slender body suddenly became an asset, some characteristic that helped shape my onstage persona. In comedy, quirks that may humble you in real life—a belly, a gap-tooth, a weird voice—can lend you an advantage onstage. Though alcoholism may destroy your private life, in stand-up it may add to your “persona,” your “voice.” Instead of someone in need of an intervention, you become Bacchus incarnate.

I wanted to do comedy because I loved, and continue to love, language. Growing up as someone who couldn’t use his body for defense, I learned to bend language in my favor, to take a potential enemy’s words and use them as fodder. If someone in class began bothering my friends and me, I would shoot back with, “Are you always an asshole, or is today special?”

Like a protagonist from a Philip Roth novel, I was tired of being perceived as the clean-cut young man. The identity had its advantages—people usually gave me the benefit of the doubt—but I grew tired of its limits. I never saw myself becoming a raunchy comic, but I wanted to scrutinize whatever struck me as odd or hypocritical. Doing so would require stepping out of my shell, an act that felt more comfortable around strangers. Looking at a crowd before going onstage, I would think, I don’t know these people—what do I have to lose?

Thus began my two-year career as an open-miker. As I continued to perform at the Laff Stop—a routine that, aside from two dollars in gas, cost me only a few hours a week—I befriended my fellow aspirants. They introduced me to other open mics, some at bars, and others at cafés. Some of them had been doing stand-up for more than a decade, stretching back to when the Laff Stop hosted legends such as Hedberg and Brett Butler. Others, like me, were still flailing away, cutting their teeth. We formed these odd friendships that took place only at comedy venues. We’d watch each other’s sets, compliment one another on the jokes that worked, offer tips on the ones that didn’t, and suggest cutting certain jokes altogether. While there was an air of competition (managers were always scouting for weekend acts), we remained friendly.

Probably my best comedy-friend from that time was a guy named Al B. Half Mexican and half Middle Eastern (I never found out which ethnicity), he looked like he was in his late twenties. Like me, he’d grown up in southeast Houston, a Mexican side of town. He wore black-frame glasses over an olive-skinned face. The inspiration for his stage-name?

“It’s there because emcees kept fucking up my last name,” he told me one night. “It’s Borzshawn. If you want to remember my full name, just think of ‘abortion.’”

His humor was like that. In 2009 he would open sets by saying, “What do Barack Obama and the Vietcong have in common?” After waiting for the audience to ask “What?” he would say, “They both whipped John McCain’s ass!”

All I knew about Al’s life outside comedy was that he worked for a law firm (as a paralegal, I assumed). Though we had different lives, he thought it was cool that I went to UH, a school he’d had “a stint” at. We got along mainly because of our similar tastes in comedy. We idolized comics such as Bill Burr and Dave Attell, performers who weren’t afraid of offending their audiences. Al and I never “knew” each other particularly well, but, as in some friendships, that didn’t matter. It was enough for us to wax about routines we’d watched or new material we were developing. In some ways, Al was the Gertrude Stein of Houston’s comedy scene. A veteran of several years, he offered advice to the younger comics, giving compliments when they were merited. He wrote a blog chronicling local stand-up events, always spreading word about new open mics.

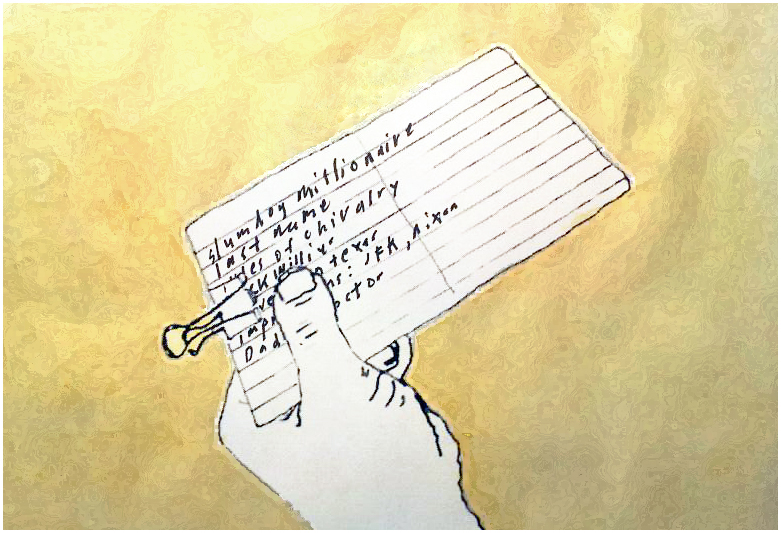

I especially appreciated that last part. At other open mics I got more time onstage, up to 10 minutes in some cases. After several months of trial and error, I developed a respectable five-minute set. In the process, I learned what I could and could not do onstage. Through some mediocre bits (one of which involved me impersonating a chimpanzee), I learned that my voice worked only when it was short and subtle. When I would write my set-list on an index card, I’d notice that it looked like a telegram from a schizophrenic:

Slumdog Millionaire

Last Name

Rules of Chivalry

Slick Willies

Traveling in Texas

Impressions: JFK, Nixon

Dad at Doctor

My style was neither physical like Jerry Lewis’s nor brusque like Richard Pryor’s. I learned the hard way that I couldn’t effectively say the words “shit” or “fuck.” They never sounded natural coming from my congenial voice. I could be The Frustrated Comic, but I could never be The Angry Comic. I strove to marry self-deprecation with commentary. I remain proud of a joke I wrote about Arizona’s prosecution of Mexican immigrants. “My last name is Garza, which in Mexico means ‘heron,’” I said. This line would typically get a laugh. What I felt good about, however, was my ability to segue into satire. “That’s weird,” I would say, “because in Arizona, ‘Garza’ means ‘show me your papers.’”

The pinnacle of my career came at the 2010 East End Cultural Arts Festival, where I was paid 50 bucks and one chicken taco to do a 10-minute set. I performed in a noisy, café-style room in front of a mostly preoccupied audience. By then, my set had become a hodgepodge of styles. One of my opening jokes went, “I’m too young to have a kid. I mean, a baby would really eat into my Facebook time.”

My jokes spurred laughs, but the sounds quickly faded back into pick-up lines and chatter. If this scene had occurred earlier in my career, I would’ve taken it as a direct judgment of my material. But by this point I knew how to distinguish a bad set from a bad room. With an indifferent crowd and guaranteed money, it’s better to just do your jokes and call it a day. I left right after my set.

Months later, I had a weirder experience at the White Swan, a smoky dive bar near downtown. My comedy-friend Mario had organized a new open mic for Thursdays. When I entered the bar for the first time, I beheld the countless beer advertisements and stickers covering its walls. Its concrete floor echoed the sounds of any shoes that walked across it. Behind the stage was painted a scene from outer space. The tableau’s left half featured a green, sphere-headed alien, flanked by stars in the distance. Near them emerged the White Swan’s fire extinguisher, ready to be pulled out at a moment’s notice.

That night only eight of us went up, including Al B. Since it was Thursday and there were no drink specials, only four non-comics showed up. Two of them were friends of a performer, while the other two looked like they had wandered in. The strangers, a man and a woman, each wore two layers of clothes, including extra jeans. They had short, square bodies and, between the two of them, about nine teeth. The woman was carrying a Tupperware jug of dry cat food. As the first few comics performed, the Cat Couple let out scratchy, exaggerated laughs, the kind that children let out when imitating adults.

When Mario brought me up as the fourth comic, he yelled, “Give it up for Edwaaaaaard Gaaaarrrrrrrza!”

My older material went over well enough. I was on auto-pilot, biding time so I could try new bits, particularly some political material.

“The other day I drove by this Tea Party rally,” I said. “They were selling these shirts that read, ‘I love my Bible—and my gun!’”

“Ooookay,” said the Cat Man.

I went on, “Because, as you know, that’s what Jesus would do: bust a cap in a mofo.”

In a room of artsy democrats, the joke did well. I even got a clap from Al at the back of the room. But I was still listening for the Cat Man.

“Ooookay,” he repeated through the laughs.

I figured that he was just talking to Cat Woman, so I started another new bit.

“You learn a lot traveling through Texas. For example—”

“Ooooookay!”

I pulled my face away from the mic and looked the man in his crazed, dark eyes.

“What’s going on here?” I said, twirling an invisible circle around them with my index finger. “Y’all got the cat food, y’all keep saying “Okay” —what’s the problem?”

Not everyone had noticed their jug of Iams, so a small wave of laughter rolled across the room. The Cat Couple just stared at me with glazed yet challenging eyes.

“Anyways, like I was saying—”

“My cat is number one!” shouted the woman. Al nearly fell off his chair laughing.

“Where is your cat?” I asked.

“At my house,” she replied, as if I’d just asked the stupidest question in the world. “Do you have a pet?” she added.

“Not right now, but I had a cocker spaniel when I was younger.”

“Didn’t you love it?” she said.

“Of course. Do you know what else I love?”

“What?”

“People shutting their mouths while I’m doing my set.”

Here I got some claps and howls.

To the rest of the crowd, I said, “I wanted to do more new stuff tonight, but now I have to deal with the Cat Couple over here.”

“We only have one cat!” the woman shouted.

“There’s no way you own just one cat. You own at least six.”

To my surprise, the Cat Couple smiled, as if their heckling had won them sufficient attention for the night. After our exchange, my prepared bits would sound contrived, so I ended my set, walking off to the loudest applause several people can muster. Silently, the hecklers walked out of the bar.

“I like how you handled that,” Al said.

“I appreciate it.”

As weeks passed, I realized that my night at the White Swan had made me a better comic. No audience ever pressed me as hard as the Cat Couple. Nevertheless, the open-mic circuit, with its late weeknights, had begun to wear me out, physically and otherwise.

* * *

In “Goodbye to All That,” Joan Didion reminds us that, “It is easy to see the beginnings of things, and harder to see the ends.” My first year in comedy was exciting and breathless. When I recall that period, I think of standing onstage and looking out into a dark room of disembodied faces, the mic poking at the bottom of my vision. I think of those moments when I would wait as the crowd finished laughing, of how, when things went well, people would smile even during the set-up. For all the strangeness of comedy, these moments—flashes of empathy, we might say—are what bring comics back.

At some point in my second year, the sheen wore off. Part of becoming a seasoned comic involves fine-tuning your material until you’re tired of hearing it. The comedian becomes a troubadour, executing tricks with a wry expertise. I recognized a more jaded comic lurking inside me. Surrendering myself to him would be to indulge in nihilism, a tendency I feared would seep into my everyday self. I strove to become more conversational onstage, but I was never able to drop my one-liners, my safety-valves. Like a young Steve Martin, I was liked for being the well-groomed guy with the silly sentences. I’d begun to forge an artistic concept, but I feared that I could only reshuffle that concept, somehow becoming captive to it. There was a wall I couldn’t puncture.

Also, stand-up had fried my social antennae. I realized that I would do certain things—go to a stranger’s party or on a questionable date, for example—only to draw material from the trifles. Friends of mine, through little fault of their own, began viewing me as Edward the Comic. With good intentions, they would introduce me to others with the sentence “He does stand-up,” to which an acquaintance would smile and ask me to say “something funny,” as if I were a walking joke machine. People always expected me to be gregarious. Most were disappointed to find out that my onstage self was real: I actually was the understated guy.

And what, I finally asked myself, was stand-up’s endgame? Let’s say that after five years I developed a professional hour of material; would I live the comic’s life? Would I travel 200 days a year to perform at clubs named Crackers, Side Splitters, and Go Bananas? Would I rise to headliner status and perform the same set five times over one weekend? Or would I, as many comics do, take my stand-up to Los Angeles and audition for bit-roles in sitcoms and movies? While my 20-year-old mind harbored pieces of these dreams, I needed something quieter, something—and I use this word only somewhat like my parents use it—stable. I needed tranquility. I needed books.

So I defected from stand-up. When Al and other comics called to ask why they hadn’t seen me at the open mics, I told them, only half lying, that I needed to study for my courses at the university, where I was suddenly a sophomore. Around this time I learned that, due to low revenue, the Laff Stop had shut down, news I found a bit symbolic. Other friends eventually stopped asking me if I still performed. I felt both relieved and released, as I still do. Besides, I told myself, I could always return to it after several years, with more life under my belt. If I had good sets at 18, why wouldn’t I have better ones at, say, 28?

I had that thought recently as I drove to a family gathering in Texas City, about 40 minutes south of Houston. A morning sun cut through clouds and post-rain steam. After half an hour, I turned onto a two-lane country road. To my right I spotted a flower-laden memorial leaning against a tree-trunk. At its center stood a three-foot-tall wooden cross, hammered into the ground and covered with dew. After thinking, How sad, I grinned. “Jews must be good drivers,” I said under my breath.

Edward S. Garza has been published in OffCite, The Crawfish Boxes, and several literary journals. He graduated summa cum laude from the University of Houston with a bachelor’s degree in English and works as a program coordinator at the campus’s Writing Center.