That night I looked up from The Dark is Rising to see my cousin Branhan walk in with a faded cowboy hat in his hand. His boots clomped on the hardwood floor. Aunt Rose talked and talked, along with my other aunts Kathy and Mary Lynn, while Branhan stood with his hands in his pockets. I only saw him every few years, when the aunts visited and brought him along. That night was the first time I really looked at him. “What’re you reading?” he asked, turning to me. I showed him the worn cover. It was from the school library. He nodded, smiled, and looked away. I couldn’t tell if he was young or old.

That night we ate fried steak, potatoes, and squash while Aunt Rose asked Branhan all about his new job at the paper mill in the town where he lived. She did not ask about his father, whom he lived with. Branhan’s father was a bad alcoholic. I kept quiet as the long minutes ticked by. Finally I was excused. Listening to the grown-ups exhausted me.

The next morning Branhan sat outside in a plastic chair, a cup of coffee steaming on the porch’s floor beside him. Aunt Rose had gone earlier to Perpetual Adoration at church. I ate my biscuits and preserves in near-silence, by myself. Once I finished, I eased out onto the porch. Branhan’s face seemed quiet, if that makes sense. Not just on that morning, but always. I remembered his sad smile from the night before and realized he had felt as exhausted as I had. He looked younger, too, in the still morning, as though he wasn’t all the way an adult. Branhan said, “Mornin, Alden.”

“Hi,” I said, and sat in a chair a few feet away. I didn’t really know what to ask him about, but he didn’t seem to be in any hurry to talk. He wasn’t like other grown-ups in that way.

“After Uncle Haig’s show is over, I was wondering if you two would go with me to the farmer’s market.”

“Uncle usually goes on Sundays anyway.”

Branhan nodded. Birds flapped up under the porch to their nest above the light fixture. “School going all right for you?” Branhan asked.

“Yeah. Are you—” I wasn’t sure at all—“Are you still in school?”

“Oh, no. I’m working. We got the horses to look after too.”

“Y’all still have horses?”

“About twenty of them. Four of them are ours, the rest are boarders. Really it’s too many on six acres.” Branhan lifted his cup and held it in both hands. “Do you ride, Alden?”

“Only that one time at y’all’s place. Back when—” I froze, wondering how to say what I wanted to say.

“Before your aunt left,” he said.

I didn’t say anything.

After a while Branhan sipped his coffee and said, “Merlin. That was the horse you rode when you were there. He’s a retired racer.”

Uncle Haig hollered outside when he was ready. He had on his overalls and a red cap to celebrate the Bulldogs beating Tennessee. We piled into the old truck, me shoved in between Branhan and my uncle. Branhan rolled his window down and watched the road ahead like an old dog. “You should’ve kept watching the game, Al,” Uncle Haig said, “They done whooped em. Just straight whooped em!” I nodded and fiddled with the radio.

We got to the farmer’s market and parked in the dirt lot. It was a sort of complex, with livestock pens, some food vendors, a small produce and flea market. We walked to the main building, where a sign advertised “Wild Mustangs, $30 and up.” Uncle Haig went off to talk to some of his friends, probably to kid one of them about the game since he wore a UT cap from time to time. I went to the chicken coops.

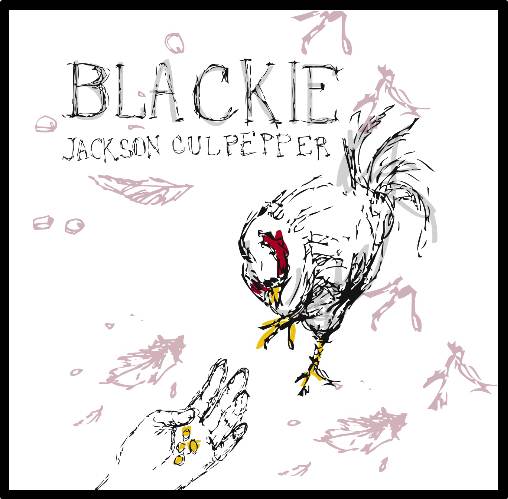

My rooster was there—black and white, no red on him except his comb. He remembered me every week when I came with Uncle Haig. Collecting a few pieces of dried corn from the ground, I held them out. My rooster came to eat them from my hand. Branhan hunkered beside me. His clothes smelled faintly of leather and new sweat.

“You got a way with animals,” he said.

“This guy knows me.” We stooped there, me feeding my rooster and Branhan handing me pieces of corn and feed that had were scattered outside the cage. I suppose I should have felt strange having him there, since I didn’t see him that often, but he was easy to have around. His jeans were frayed at the side stitching and his boot heels were worn white.

It was something about sadness. Not many people in my family seemed to understand how sad people need quiet to be happy. The rest of them drank at every reunion like my parents and Branhan’s dad didn’t exist. Like there wasn’t anything to it.

My rooster took a few more pecks at my hand and trotted off. We rose and walked past a booth selling quart jars of honey and another selling sweating glass bottles of milk, unpasteurized. Around the larger pens we heard a commotion: the snorting of horses and shouts of people trying to contain them. We leaned against a rusty pen section to watch.

Twenty or more horses eddied in the main arena. They called to one another. Men walked back and forth with lead ropes and halters, wrestling horses’ heads and dragging them out to a trailer. The process didn’t look fun for the men nor the horses. “They’re having a hard time, aren’t they?” I asked Branhan.

He nodded. Dust from the pens fell over us and gritted into my clothes. “You see a good one?” Branhan asked. I looked, trying to distinguish between one mottled coat and the next. I didn’t know much about horses but I saw a rearing head, all white with a blue eye, wild and confident. I pointed the horse out to Branhan and said, “He would be a good one. Tough, though.”

Branhan looked across to other enclosures. “Reckon they’re using that round pen?” he asked.

“I don’t think so,” I said, but Branhan was paying attention to the horses.

After a while I got bored and walked on. I went to the food shack and bought a hot dog and some sweet tea. People walked by me in overalls, most of them fat.

By the time I got back, Branhan was in the round pen with the blue-eyed one. He had a length of rope in one hand and his back to the horse. It trotted back and forth, looking at him. I watched for fifteen minutes or so, as the horse slowly calmed and nosed dry manure in the pen. Branhan stood, coiling and uncoiling the rope, not speaking. The horse crept closer to him, straining its neck to sniff more of his scent. Branhan didn’t move or turn around. I was glad he wasn’t kicked and trampled but I wondered what he was thinking.

Walking down the concrete aisle, I looked for Uncle Bobby. I had an idea where he would be, but I didn’t want to go. If he was there I could ask how much longer until we left. I pushed the crooked door open and peered inside. The room was utterly dark at first, until my eyes adjusted. I scuffed my feet on a rough concrete step going down. There was cigarette smoke, and finally I saw Uncle Haig’s red cap, jerking back and forth.

Men yelled and cussed, spraying spit and tobacco juice. They had just put in the next round of cocks and I stood on tip-toes to get a look at them. The first flew up: crimson with iridescent black feathers in its tail. They had gaffs on it. The cock squawked and hopped after the other one. Once I was close enough I saw that the second cock in the arena was mine, the black and white. He ran from the crimson—he didn’t fight at all, just tried to get away. The men cussed and threw cigarette butts and spat tobacco juice that stained his feathers. The crimson pounced him again and again. Blood flecked the sand, darker than the crimson, more red than the tobacco spit soaking into sand. My black and white stumbled, flapped its wings, danced at the edge of the arena. He tried to jump out but one man slapped him. My rooster moved more and more slowly, until the man who had thrown them in at the start climbed in and grabbed him. Half the men booed and the rest cheered. I saw Uncle Bobby rubbing his hands together the way he did when he was excited.

I followed the man who held my rooster. Outside he dropped him in the dust. I went over and started wiping off all the grime. It stained my hands. My rooster’s small chest rose and fell quickly and his eyes blinked. He wasn’t moving his head. I asked the man if he thought my rooster would be okay. The man looked at me and walked back into the shed. I tried to hold the places where my rooster bled. After a while his breathing became more shallow. Finally his eyes stopped blinking. His chest still felt taut, still had its weight. I held my rooster to me and cupped his head where it lolled.

People bury dogs and cats. I wondered, does anybody bury roosters?

I picked him up and walked to the edge of the woods behind the farmer’s market. It was late afternoon by then and the lowering sun lit up the leaves. Patting down a tuft of long, soft grass, I lay my rooster there between two pecan trees whose limbs hung down and cooled us. Warm wind whirled the boughs, a sound apart from the distant bustle of the farmer’s market.

They say the first part of childhood you lose is that sense of no-time, when each moment is a long dream. The brilliant sunlight also dims, or escapes your notice. I walked back.

At the pen, Branhan moved in circles, clucking his teeth or saying “whoa.” The blue-eyed horse moved back and forth. Branhan held the loose rope in one hand, barely raising it. I saw other men loading their purchases into trailers, pushing and shoving, dragging on lead ropes and slapping rumps to get the animals to move. A few horses reared.

Booths closed down. People packed up their boxes of goods. Trucks and new SUV’s glided past on the highway. I thought about those families, happy in their new things, going home to a normal life without glass doorknobs, drafty windows, tub baths—back to parents. I envied those kids, whose homes were filled with many good things.

Uncle Haig came up behind me. “What’s your cousin doing?”

I didn’t look at him. I didn’t want to look at him.

Branhan turned in the center and the horse ran around him at the rail. “You ready?” shouted Uncle Haig. “You two go on,” Branhan said, “I’ll be there after while.”

Uncle Haig looked around and seemed to grasp what was happening at the pens. “Did you buy that horse?”

“Yessir, I did.”

“Son, we ain’t got a trailer. How were you planning on getting him back?”

“I can ride her.”

Uncle Haig laughed, a sound like a grunt. “You gone ride your horse back along the highway?”

“Yessir.”

Uncle Haig made a soft, incredulous sound. Branhan did not move out of the pen, he didn’t even pause in what he was doing with the horse. There was a tension and energy to his body that hadn’t been there, or a power that had previously been muted. Uncle Haig shrugged and we got in the truck.

At home, Aunt Rose had left a few pimento cheese sandwiches on a platter under plastic wrap and gone to her book club. She would come back giddy with the wine they drank. I lay on my bed, trying to read, but ended up just looking at the ceiling and the long crack in it.

I don’t know how long I was asleep before I heard hoof falls on the gravel drive. The horse blew and Branhan muttered something to it. I ran downstairs. Sure enough, there was Branhan astride the mustang. He sat bareback and used an old rope for reins. He stopped me by holding his hand up, and slipped off the animal’s side. “Real slow and gentle, Alden, she’s green.” I nodded and inched forward, pushing the screen door aside. The horse was smaller than it had looked in the pen. I could look straight over her shoulder. She shook her head from side to side. Muscles hung and twitched on her chest. “That’s it, Alden, gentle. Let her smell your hand.” I almost jerked back when that heavy head turned towards me and saw me with its bright blue eyes. She stretched to sniff me, nostrils opening wide. Her breath was warm and smelled warm. “Pet her real easy on the nose. You’re doing fine.” It felt soft. Her lips smacked. Branhan smiled. He handed me the reins and went to shut the gate. “I hope Aunt Rose don’t mind if I let her graze in the yard for the night. I hope she don’t shit—crap in the yard.”

“How did you do that?” I asked. “How did you tame her that quick?”

Branhan wiped sweat from her neck with the flat of his hand. He said, “It’s all about listening. That’s all it is.”

He didn’t say anything more. I went to the other side and wiped her sweat off like he had. She jerked her head away and Branhan spoke to her. He told me, “Be real slow, she’s getting used to all this. Keep one hand on her so she knows where you are.”

“Does she have a name?”

“Not yet.”

“You should call her Blackie.”

“Even though she’s a paint?”

“Yeah.”

Branhan slid the halter off her face. He touched her ears, whispering to her. “Sounds good to me,” he said.

We walked back inside and I turned to go up the stairs. I looked back once at Branhan. His hat was off, his hair damp with sweat. He smiled that quiet smile, not for me but for himself, and walked to the shadows where the couch was.

I lay in bed listening to Blackie graze. It was a calm sound, like beach waves but softer.

They say the first part of childhood you lose has to do with time. Looking out at the moon, I didn’t feel time at all. But I began to guess, with the foolishness of a child, that some lost things have a way of reappearing when you’re ready for them.

Jackson Culpepper grew up in the South and is just fine being stuck with it. His work has appeared in Armchair/Shotgun, Real South Magazine, and other publications. He was raised in south Georgia, where most of his stories still live, but now resides in east Tennessee with his wife, Margaret Culpepper, two horses, and two dogs.